Interviews

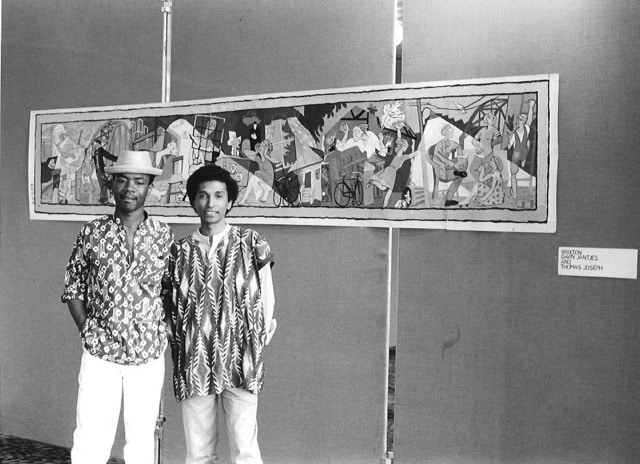

Gavin Jantjesthe Greater London Council’s Anti-Racist Mural Project commissions.

In 1984 The Greater London Council (GLC) decided to commission established artists with a reputation from the Afro-Caribbean and Asian communities, working to a very high standard, to paint murals about the community’s history, its strength and survival in London. Four murals which would capture and reflect their respective areas were commissioned: from Keith Piper and Chila Kumari Singh Burman in Southall, a mural by Shanti Panchal and Dushela Ahmad in Tower Hamlets and a third by Lubaina Himid and Simone Alexander in Meanwhile Gardens, Notting Hill. The fourth, acknowledging the vitality of Brixton, would be by Gavin Jantjes assisted by Tam Joseph.

Gavin Jantjes

Gavin was born in Cape Town, South Africa, “in a part of the city which no longer exists, called District 6. District 6 was evacuated and bulldozed by the apartheid state because it had the homes of some 180,000 non-white residents. They were moved out of the centre of the city to an area called the Cape Flats.” Gavin came from “a very working class background with a rich cultural mix of all sorts of religions, all sorts of people, all sorts of professions.” His parents and grandparents were ‘not interested in the visual arts’, though he had an uncle who was a photographer. Jantjes went to the Zonnebloem Boys School, an English boys school set up by the Anglican Church, and afterwards attended Harold Cressy High School. “There was a great community spirit in District 6,” he says, “and I attended a children’s art centre, one of the few children’s art centres in South Africa at the time, from the age of 3 until I left when I was 22 years old. So my art experiences began at a very early age.”

Following this, Gavin studied art at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, in the University of Cape Town, graduating in 1968, and in the summer of 1970 won a scholarship to study in Hamburg, Germany, experiences which he notes were very rare for a “so-called non-white or Black artist as these terms were applied.” His printmaking work in Germany led to a solo exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London in 1976, where he met “a number of involved and engaged activists and politically motivated artists such as Rasheed Araeen, the art critic Guy Brett and the performance artist David Medalla.” When Gavin came to live in the UK in the early 1980s, he also worked with the Tomlin Square Print Cooperative. In 1980 he joined the Edward Totah Gallery which forced him to leave Germany.” and he moved to the UK to live in Christian Malford, a village close to Chippenham in Wiltshire. By this time, he was exhibiting his silkscreen print work “all over Europe” on the subject of the anti-apartheid struggle. This work he says, “was very topical” as South Africa was considered something of a “pariah state in turmoil” in the early 1980s. In the Late 70s, Gavin began to make paintings, but “had never made a mural or painted on anything that I would call a mural.” He was invited by Parminder Vir and Paul Boateng at the Greater London Council (GLC) to create a composition for “a mural about South London, and the upheavals in Brixton.” When his design was accepted by the GLC he proposed that Tam Joseph should be his assistant to paint the mural.

Tam Joseph

Tam was born in Dominica in 1947, a country which he remembers both as a beautiful Island, and a place marked by the vestiges of colonialism and slavery. His father arrived in Liverpool in 1953, part of the first generation of Caribbean migration to the UK in the 1950s. He was a man skilled with his hands and worked as a cobbler. Tam’s family followed shortly afterwards on an ocean liner that docked in Tenerife, Genoa and Southampton. They moved to Highbury in North London when he was aged seven. He went to school at Drayton Park in Highbury where he was the first black child in the school, and there were only twelve black children in the boys secondary school he later attended in Holloway Road. Tam’s parents were poor, hard-working and frugal with money, “My mother and father never took a holiday,” he says “immigrants worked hard, for them enjoyment was a sin. You always saved for a rainy day. They were very careful.” He says that his mother and father would “probably have been considered middle class.’’ His father was “a reader” and his parents voted Labour. He noted, “People in the Caribbean knew a great deal about worker’s rights, when we came here we naturally gravitated towards union.”

In the late 1960s, Tam developed his skills by joining life classes with the Islington Art Circle, where he felt welcomed for his commitment to drawing, despite being the only young black artist amongst the group: “My peer group was 60 years older than me but it was great, I picked up a hell of a lot very quickly and I learnt more about drawing there than I did in art school.” Attending art school, Tam recalls that most of his contemporaries had been to public school, but he had “barely heard of public school.”

He considers artistic skill a ‘great leveller’, “I draw and paint a lot better than a lot of people and always have done, that means I fit anywhere – it’s a great leveller – I could draw, and paint and sculpt, that’s where my class is. It’s not measured by the amount of money in my pocket, because if it did, I’d be in a lot of trouble! My main concern has not been to make a lot of money, but to express myself.” Tam undertook other work to support his art career, such as working as a ‘paint and trace’ artist on the animations for The Beatles’ film, ‘Yellow Submarine’. He studied typography at the London College of Communication and this led to work in publishing as a layout artist and cover designer for successful political and economic monthly magazines such as ‘Africa Magazine’ and ‘West Africa’.

‘The Dream, the Rumour and the Poet’s Song.’

community consultations and the design’s development

Together Gavin and Tam consulted various groups in the area, particularly people – like Tam’s family – who had come from the Caribbean Islands to the UK at the end of the World War II. A copy of Picasso’s 1937 painting, ‘Guernica’, copied onto a wall in Guernica was an inspiration for the design as well. Gavin said, “All the various people we spoke to in the area, the guys on the street, the community leaders in the town halls, the people at the health and sports centre, the Carnival band groups, the local police, the church people. All of their ideas were somehow touched on, and I thought initially that this would be an impossible task, that there were too many things, but somehow we managed to get a bit of all of that into the design.” It was titled, ‘The Dream, the Rumour and the Poet’s Song.’

The artists were also required by the GLC to consult with the police about the design of the mural. Gavin recalled that “The police in particular were very worried about the possible depiction of police violence against the Black community at the time of the Brixton riots, and were asking to see exactly what the design looked like. We refused to show them the design, saying that they had to trust us not to paint the police in a manner that was untrue, and that’s where we left it.’

preparing the wall

“The mural was to be located on a long wall at 50 Railton Road in Brixton, next to a small public square and beside a children’s kindergarten. The GLC negotiated with the owner of this wall to allow us to use it. The wall was specially rendered and treated, initially to use a specific dyeing process where you impregnated the render with pigment, because it had a longer life and was more colourfast. In the end, the paint company could not deliver the colours on time and commercial acrylic paint was used, in order to meet the GLC’s deadline for the mural.”

finding the colours

After the wall was rendered it was washed down and cleaned, then given three or four layers of gesso, after which Gavin and Tam began to mark up the drawing onto this wall and paint it.

drawing the mural

Tam recalled, “There is a process in creation of a mural, you start off from rough, everyone does a rough. The rough is 1/10th or 1/20th or 1/50th of the whole thing, and it is then projected to the scale required. And then all the elements have to be transposed from the rough very carefully, once you’ve done that, it’s like walking up and down stairs.” Tam said that his practical experience working as a ‘paint and trace’ artist on the animations for the Beatles’ film ‘Yellow Submarine’ had prepared him well for the task of scaling up and following Gavin’s design.

challenges

Because most other murals in London at the time were above head height, on the sides of buildings high up, whilst theirs was painted at street-level, the artists feared that it would be vulnerable to vandalism. Noting that “most murals were being targeted and defaced by neo-fascist and right wing groups who didn’t like the images.” They covered the mural with layers of anti-graffiti spray, but Gavin later judged that this had been unnecessary, as after four years, the mural remained intact. The two artists had painted the mural in six weeks over the summer of 1985, using a moveable scaffold, with the bright sunlight and heat sometimes presenting a considerable challenge.

painting the mural and the public’s reaction.

Gavin Jantjes noted the acoustic qualities of the wall, which would often reflect the sound of people’s conversations in the square nearby while the artists worked. Gavin recalled, “So very often there would be elderly people sitting on the benches, talking about Tam and myself, working on this scaffold and painting this mural and what the mural depicted, and some of these stories were both hilarious and encouraging, because we seemed to have got it right from the comments we were hearing.” The artists were also visited daily by the local police, who they used to see patrolling the area and talking to people in an attempt to regain the trust of local residents, “It was quite clear that the police were doing a tremendous job trying to convince the local public that they were on their side, but I don’t think very many people at that particular moment in time trusted the police at all.”

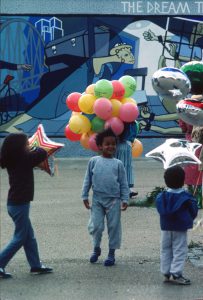

The mural was officially opened by Paul Boateng in Autumn 1985 with a street party and local carnival band.