Murals

David Cashman and Roger Fagin created the Islington Schools Education Project in 1975.

David Cashman studied painting at the Royal College of Art, graduating 1964. Roger Fagin was a graduate at St Martin’s School of Art, a sculptor and founder member of the Stockwell Depot Group working and exhibiting in South London in the 1970s. They taught together on the Foundation Course at St Martin’s and created the Islington Schools Education Project in 1975, when they began to work at Laycock Primary School in Islington. Their project would aim to create works of art for a school in a deprived urban area, a project that would also develop a strategy for collaboration, learning and action.

“The idea for Laycock originated in an experiment we had been involved in for some time. As art teachers we both felt increasingly frustrated by the expectations and limitations of our roles as artists within a system where values centre on exclusivity and competition. We started thinking of ways in which we could set up projects and work with students towards a common ideal. In 1973 we began a project at St Joseph’s Primary School in Covent Garden. The plan was that we would take the playground – which was a tiny narrow tarmac area surrounded by high brick walls and extremely bleak and depressing, and work with students on transforming it. We were shifting our role away from traditional teaching on an individualistic and divisive basis, to a collaborative one, in which the sharing of experience created a relationship that, was more positive and productive. We worked as designers, consulting with the children in the school about transforming the playground environment, and then brought the project into being with students.” Rather than freedom, they gave the pupils structures to work within, boundaries which produced surprising insights and discoveries for children and artists both. Through that experience they proposed to the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) to run a two-year experimental project at Laycock Primary School in Islington, in which children, staff and hopefully parents would collaborate in design. As with the St Joseph’s project the artists brought in students to take part.

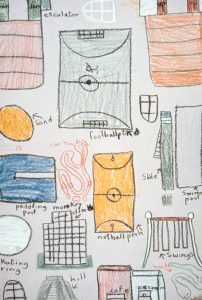

They wanted to find out how children perceived their school environment, making drawings and large-scale models in the classroom. They asked the children to describe their ideal environment and to draw it. Their choices included a ghost house, a castle, nature and animals, a teacher trap (a hole with spikes) and a lover’s leap (with a net to catch foolish lovers). At Laycock there were no formal art lessons, so drawings were part of all classes. Many images were discovered from maths, perspective lessons and from looking at advertising.

They wanted to find out how children perceived their school environment, making drawings and large-scale models in the classroom. They asked the children to describe their ideal environment and to draw it. Their choices included a ghost house, a castle, nature and animals, a teacher trap (a hole with spikes) and a lover’s leap (with a net to catch foolish lovers). At Laycock there were no formal art lessons, so drawings were part of all classes. Many images were discovered from maths, perspective lessons and from looking at advertising.

One of the first things to do to transform the school was to take the classroom game where one child draws round another, and then paints themselves – or the other – onto the walls. This they did all round the school, inventing their own positions, costumes and colours. The idea was that these portraits would continue – each generation coming through with their images – that this was a way of establishing the children as the main agents of change. For the building the portraits declare its identity as a school – and for the child a literal impression of yourself on your environment forms a connection and ownership. The children explored structures to play on, scaled down models made of Dinky Toy tyres and pieces of wood. They made and decorated a model of a train, and imagined and made drawings different games that could be played. And from the models the artists then built structures of real tyres and timbers and painted the concrete train.

The disused toilet block in the playground was due for demolition but when the artists analysed the movement of children at playtime they found it was the most visited area. So it was reprieved and David Stone, a student artist in the team, worked with seven to eleven year-olds exploring the toilets’ conversion possibilities on the ‘Ghost House’ theme. A multi-coloured ‘Snake Mural’ was painted on the outside. Inside, from shadow projections ‘monster’ masks’ made by pupils, ghostly overlapping shapes were painted, and an internal switchback from rope and second-hand timber, and hiding places and spy-holes were devised.

The disused toilet block in the playground was due for demolition but when the artists analysed the movement of children at playtime they found it was the most visited area. So it was reprieved and David Stone, a student artist in the team, worked with seven to eleven year-olds exploring the toilets’ conversion possibilities on the ‘Ghost House’ theme. A multi-coloured ‘Snake Mural’ was painted on the outside. Inside, from shadow projections ‘monster’ masks’ made by pupils, ghostly overlapping shapes were painted, and an internal switchback from rope and second-hand timber, and hiding places and spy-holes were devised.

A perimeter wall was built by parents, and children designed the garden within from measuring, then making models and drawings of its layout and planting. A maze – to assist with numeracy – was designed by the artists, and a castle was built, initiated by staff interested in drama. There were classes too in pottery and children’s ceramic plaques decorated the walls.

The planning of the front of the school was very particular. David Cashman said, “When we first looked at the building, we said this is a living piece of architecture and we must respect its language, which is its bricks. We will make an image that will connect with it. So the tall double gable mural project of 1976 was to be made West Indian style, which also relates to weaving, with each brick painted individually. At first Roger wanted to paint his design – a rainbow – rather than the children’s, and we got into a deep conflict about it, and the way that we dealt with that was to go back to the school community to discuss it with them and decide. Because for the first time we had ceased to be specialists who knew all the answers.  But out of that grew a very real involvement of the school; they really got to talk about the quality of the images, the way they were made and what they meant – and meant for the future. And in the end it was a great exercise in public participation.” Then the decision was made that the children would do the designs. They each made their own on a printed brickwork grid with water colours. Over three hundred were made and sixteen were selected to be painted on the wall. “There was,” said David, “an extraordinary richness and diversity in the children’s work – they took the language of the grid and pushed it around. Transcribing each design onto the gables was an insight into the mind of its creator – very exciting. The decision to use children’s designs for the front was taken in the belief that the facade functions really as a face for the school, showing as clearly as possible the kind of activities that go on inside. Roger and I painted it off an enormous scaffolding tower, on the front of the school. It took five months to execute.” The response was very direct and encouraging from staff and pupils. “Some architects from North London Poly walked around and said, ‘This is incredible, there’s feedback going on all the time all round you.’” Every child felt they had contributed personally.

But out of that grew a very real involvement of the school; they really got to talk about the quality of the images, the way they were made and what they meant – and meant for the future. And in the end it was a great exercise in public participation.” Then the decision was made that the children would do the designs. They each made their own on a printed brickwork grid with water colours. Over three hundred were made and sixteen were selected to be painted on the wall. “There was,” said David, “an extraordinary richness and diversity in the children’s work – they took the language of the grid and pushed it around. Transcribing each design onto the gables was an insight into the mind of its creator – very exciting. The decision to use children’s designs for the front was taken in the belief that the facade functions really as a face for the school, showing as clearly as possible the kind of activities that go on inside. Roger and I painted it off an enormous scaffolding tower, on the front of the school. It took five months to execute.” The response was very direct and encouraging from staff and pupils. “Some architects from North London Poly walked around and said, ‘This is incredible, there’s feedback going on all the time all round you.’” Every child felt they had contributed personally.

The ILEA were pleased with the project. When its two years were coming to an end, the staff who had been involved all through took over. The ILEA and the Greater London Council were discussing how to extend and develop the team’s work. The artists said, “We’ve already started working in a number of other schools in the area, our role being more consultative than at Laycock. The staffs have expressed enthusiasm for bringing about change in the environment though with some anxiety about the responsibility.” New proposals emerged which shifted the problem to a wider area: the relationship of the school to the community. “To seeing the school as a resource which they can use. Our function will be as a catalyst, to be involved as the boundaries of the school expand to meet the community, and as people seek to shape their environment.”

Talking of different types of murals David Cashman spoke of their distinctions. ”There are those that are the product of participatory processes and communal creative activity, whether it’s with kids or adults – lots of possibility of interaction. There’s another sort, which I’d call an interpretive one where the artist seeks information from the environment or the community where they live and they’ve got a contract with the community to interpret their needs and concerns. Then there’s another kind of artist who isn’t any of those things, who’s projecting an internal image out onto the environment, and that worries me.”

Talking of different types of murals David Cashman spoke of their distinctions. ”There are those that are the product of participatory processes and communal creative activity, whether it’s with kids or adults – lots of possibility of interaction. There’s another sort, which I’d call an interpretive one where the artist seeks information from the environment or the community where they live and they’ve got a contract with the community to interpret their needs and concerns. Then there’s another kind of artist who isn’t any of those things, who’s projecting an internal image out onto the environment, and that worries me.”

About art’s focus on individualism, Roger said, “The gallery system is not nourishing, the way our system operates now involves an appalling wastage. It is reflected right through the education system – wastage in further education is a small proportion of wastage in talent in society at large. The way we work is contrary to specialisation. We are trying to develop our role into a multiplicity of functions, so that our work as ‘artists’ isn’t separated from our educational and administrative function, or the physical labour we do, or our interactions with people with other skills. What we are doing is clearly not original or unique to one individual but to break down those concepts to create something which is the end product of a process which involves the uniqueness, originality and creativity of lots of different people interacting.”

David Cashman is equally assertive about the need to work collaboratively with other specialisms. “When you are a muralist you have to be diplomatic because you are going to be talking to a lot of people who don’t understand what you are saying, and there’s no reason why they should and you have to communicate with them too. Our experience is that we get help when we ask for it, and we show there is positive energy on the move. We haven’t said we can’t get on with architects and planners and bureaucrats. We’ve gone out and taken them on. Because there are people who have vision and positive creative energy and they need to give it space to let it grow!”