Murals

Unionist mural painting

In 1921 the boundaries of the new Northern Ireland state were drawn in such a way that a Protestant majority was guaranteed. Maintaining that majority involved repressive policing, gerrymandering, and discrimination in allocation of public housing and jobs. Political power was monopolised in the one-party unionist state, protected by an overwhelmingly Protestant police force.

In this situation, unionist culture had pride of place. The annual cultural high point was the celebration on July 12th of the victory of Protestant King William over Catholic King James at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. Streets were decorated with bunting, flags and arches, kerbstones were painted, bonfires were prepared, and on the day itself towns and cities were brought to a standstill as members of the Orange Order, exclusively Protestant and male, dressed in dark suits, marched behind bands playing military-style music.

In 1908, as part of these annual celebrations, Belfast’s first mural was painted by a shipyard painter called John McLean; it depicted King William at the Battle of the Boyne. For the next sixty years images of King Billy, as he was affectionately known, were painted or repainted repeatedly on the walls of working class neighbourhoods in unionist areas (see figure 1).

Figure 1. King Billy mural, Coleraine, 1982

Figure 1. King Billy mural, Coleraine, 1982

The King Billy murals spoke of British and Protestant identity and of community pride as each working class area vied with its neighbours to have the most impressive mural. But at the core of the murals was a triumphalist celebration of colonial victory; once upon a time the natives were defeated and the settlers were victorious. On each July 12th march, each mural reminded everyone concerned that centuries later an unbalanced power relationship remained.

King Billy was the overarching symbol encapsulating all of this. He spoke to determination and victory, to survival and triumph. He in effect personified the unionist community and state. Few other themes managed to appear in murals. The main exception was referencing the Home Rule crisis and the role of the 36th Ulster Division in World War 1. The first spoke to the unionist determination to remain British at any cost, and the second to the sacrifice that unionists had undergone in support of the British war effort, in effect, reminding Britain that it owed the unionists.

In the late 1960s a civil rights campaign seeking equal citizenship for nationalists/Catholics began. Some unionist leaders supported reforms, if only to placate protesters, while others maintained that there was to be ‘No Surrender’, an-age old unionist slogan. Unionist unity was dealt a mortal blow and one of the most obvious casualties was the principal symbol of that unity, King Billy. Fewer King Billy murals were painted and many older ones were no longer repainted annually.

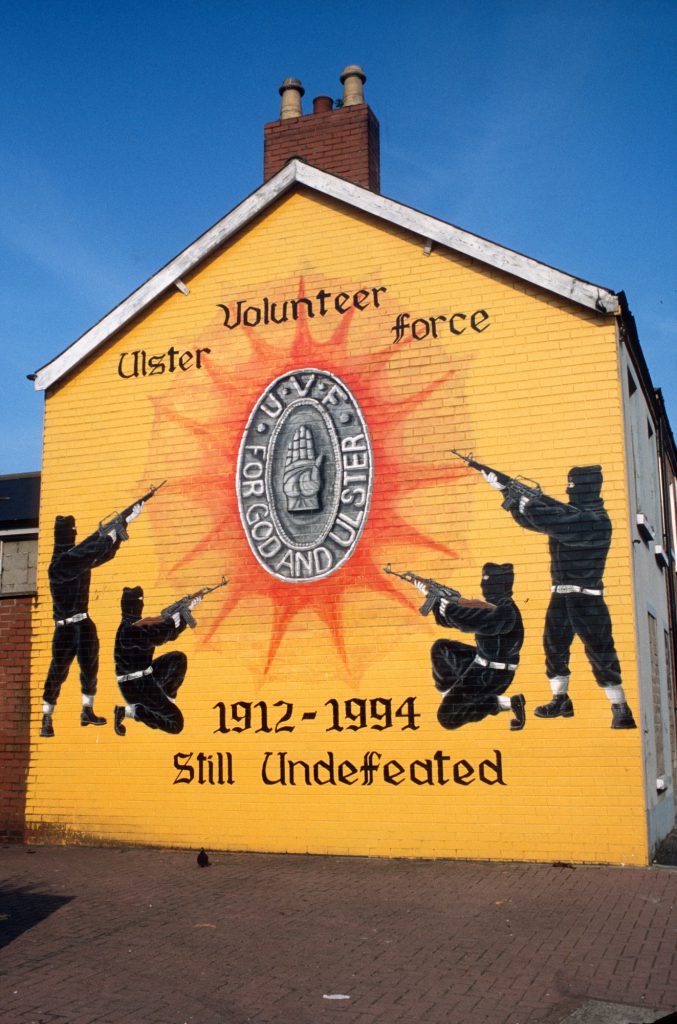

The scene changed even more radically in the mid-1980s. In 1985 an Agreement between the governments in London and Dublin allowed the government of the South an official say in the affairs of Northern Ireland for the first time. The unionist reaction was animated and often violent. Part of that reaction was that the painting of murals in unionist areas came under the monopoly control of paramilitary commanders. From the summer of 1986 on, no murals were painted in those areas without their express agreement. For the next two decades the vast bulk of loyalist murals depicted masked and armed members, advertisements for whichever paramilitary group held dominance of any particular area (see figure 2).

Figure 2. UVF mural, East Belfast 1994

Figure 2. UVF mural, East Belfast 1994

Republican mural painting

With partition, nationalists found themselves in a state to which they did not wish to belong. They were marginalised, discriminated against and depressed socially, politically and culturally. In this situation there was little political space to paint murals through the first six decades of the Northern Ireland state. The situation changed in 1981. Republican prisoners went on hunger strike demanding the return of political status. Between May and October six IRA and four INLA (Irish National Liberation Army) prisoners died before the strike was called off.

As the hunger strike developed, it sparked a massive grassroots response from the wider nationalist community in the form of marches, protests, pickets and other forms of public manifestation. Younger republicans began to paint slogans on the walls and soon pictorial elements were added. The republican mural tradition was born.

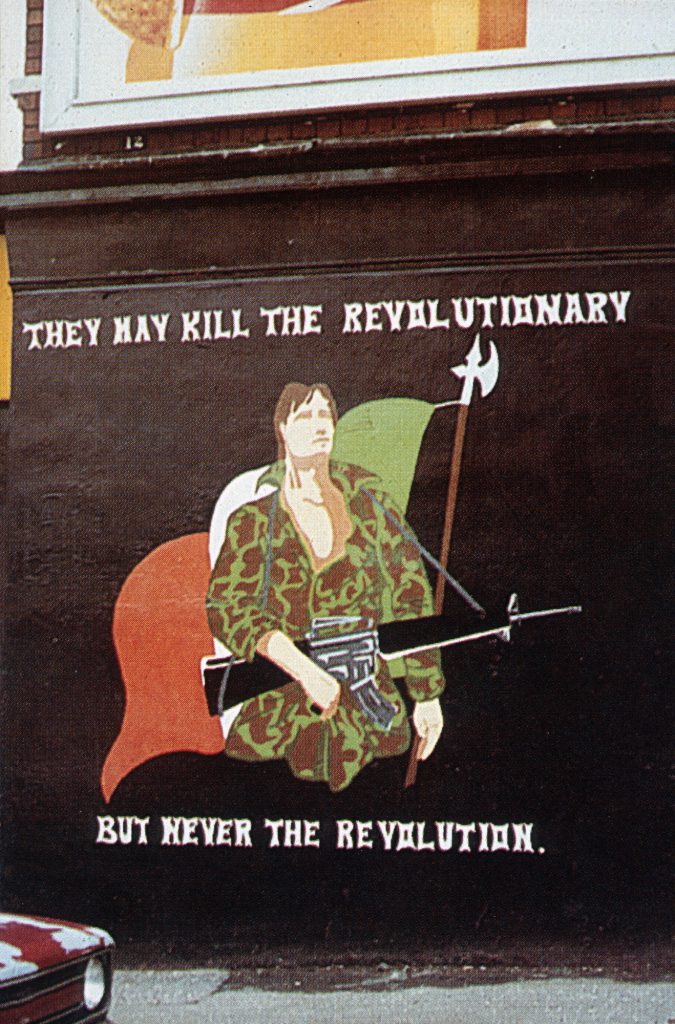

Figure 3. Republican prison protest mural, West Belfast 1981

Figure 3. Republican prison protest mural, West Belfast 1981

The most common theme in these early murals was the hunger strike–portraits of each of the ten, representations of both resistance and suffering, the overall message being that the prisoners would defeat not only the prison system but British involvement in Ireland (see figure 3). Thus, even though many of the early murals displayed a humanitarian message – ‘Don’t let them die’ – there was no attempt to play down the fact that the reason for their imprisonment was armed resistance (see figure 4). When the hunger strike ended, this message of armed resistance continued. However, it never came to dominate the republican mural scene to the extent it did in the loyalist community. Compared to loyalism, republicanism is a relatively broad political ideology. Thus republican socialists, feminists, trade unionists and others displayed their messages on the walls alongside the pro-IRA and pro-INLA messages. Republican commanders never sought monopoly control of the walls.

Figure 4. Pro-IRA mural, West Belfast 1981

Figure 4. Pro-IRA mural, West Belfast 1981

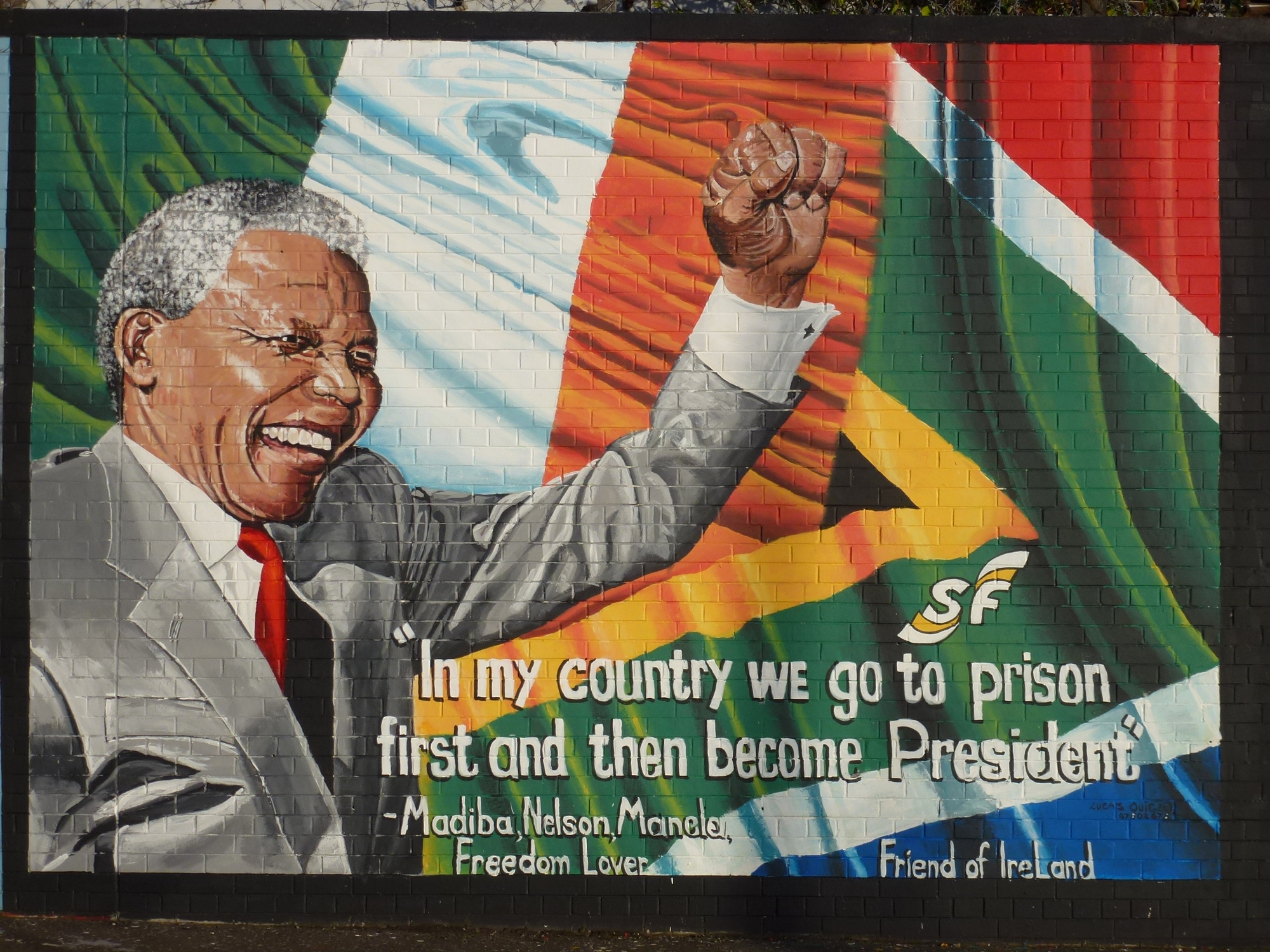

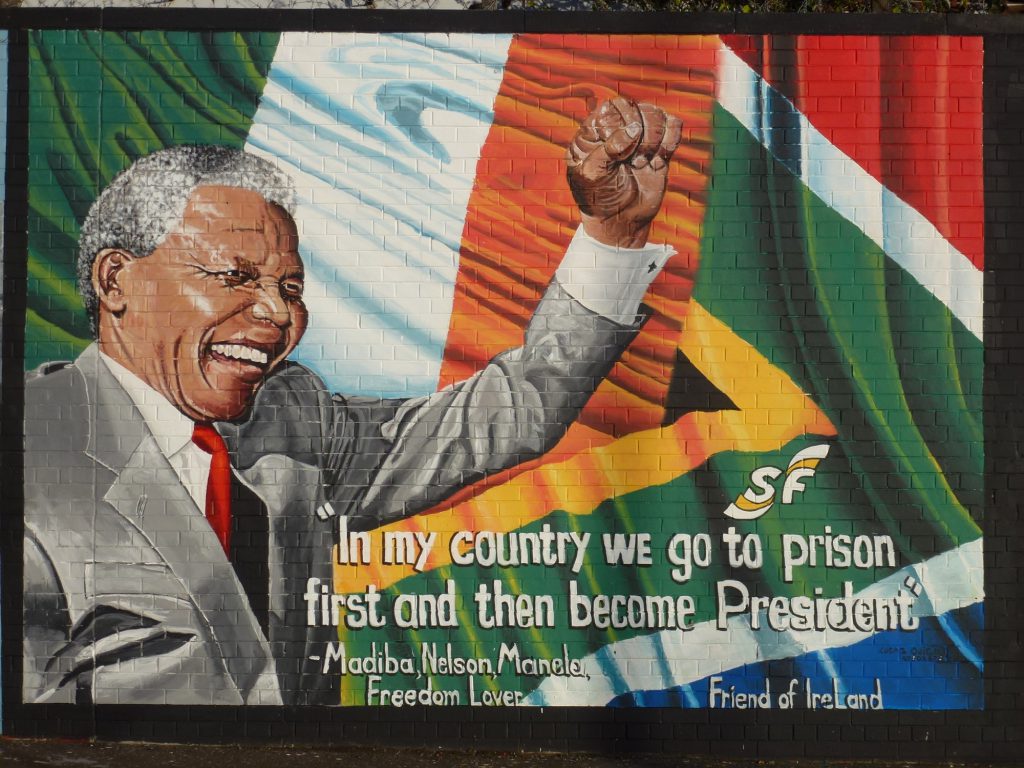

Republican muralists urged voter turnout for elections, painted heroes from Irish history and mythology, commented on current political developments, condemned state repression and killings, and proudly paraded their identification with other anti-imperialist struggles in places like Palestine, South Africa, the Basque Country and Cuba. The relative political freedom they had affected artistic style, so that their murals were often more colourful and imaginative than those of the loyalists.

Mural painting and the challenges of peace

At the end of August 1994, the IRA declared a ceasefire, followed six weeks later by the loyalist paramilitary groups. Republicans had been persuaded that doors would open were they to declare a ceasefire and in the immediate aftermath of the declarations there was a definite air of promise and expectation. Later, republicans were to argue that political progress was not as speedy as they had been led to believe. Consequently, the ceasefire broke down in February 1996. However, the efforts of the newly-elected Labour government in England saw a new ceasefire emerge in July 1997. Less than a year later all-party talks led to the Good Friday Agreement, pledging Northern Ireland parties and the British and Irish states to power-sharing in a devolved Northern Ireland assembly.

For many of the republican rank and file and their supporters and voters, these were unnerving times. The new parliament was to meet in Stormont, the seat of the previous unionist government and a long-standing symbol of exclusion for nationalists. Later, the evolution of the peace process required the republican party, Sinn Féin, to take the radical step of supporting the police, albeit a reformed police service. A long and complex set of negotiations resulted eventually in the IRA decommissioning its weapons and explosives, and finally, in 2008, the disbanding of the organisation.

Republican muralists played a key role in calming nerves and persuading people to go along with these momentous changes, politically educating the grassroots about the compromises needed in a peace process. One technique was to remind people that the goals were still the same: equality in the North, and ultimately a united country. There was no sudden change of iconography: no butterflies, rainbows, sunrises, children holding hands or other superficial symbols of peace. Instead, some murals acted as a call to the state to deliver on the promises of the Agreement.

In addition, old symbols could take on new roles. For example, the continued painting of the image of Bobby Sands was not to indicate stasis or even worse, a pining for the reassurances of binary conflict. Rather, it was a form of reassurance and persuasion (see figure 5). The message in effect was this: you stuck by Bobby Sands during the hunger strike; you supported the liberation struggle of which he was part; now we have moved into a new phase where we are prioritising different means to the same end of liberation; peace is not a sell-out but a new opportunity; join us.

Figure 5. Portrait of hunger striker Bobby Sands, West Belfast 2015

Figure 5. Portrait of hunger striker Bobby Sands, West Belfast 2015

Republican muralists took a decision no longer to paint hooded men or guns. There were two exceptions: first, historical murals, for example, depicting fighters in the Easter Rising in 1916; and second, memorial murals, often site-specific, portraying dead comrades from the recent conflict. In both cases the guns depicted were not contemporary, were not for current use. Republicans could make this major step because of the range of other themes on which they could paint–Irish history and mythology, local current affairs and commemorations, as well as international struggles (see figure 6).

Figure 6. Portrait of Nelson Mandela, West Belfast 2013

Figure 6. Portrait of Nelson Mandela, West Belfast 2013

Loyalist muralists were in a more difficult position. Their ability to match the range of republican themes was severely limited. Their grasp of history was less firm, and they had limited scope to draw on mythology. Furthermore, loyalist muralists could not easily depict international comparisons. The only contemporary parallel referenced in loyalist murals is to Israel. For some there is a genuine sense of connection, but for others simply a retort to the republicans’ identification with Palestine.

Given the fixation on military imagery, taking the guns out of loyalist murals is highly problematic. The fear is that it would leave almost nothing else to be painted. The message to loyalist commanders to take the guns out of the murals was in essence a demand to return mural painting to the wider unionist community where the hopes and fears of the whole community could be expressed rather than simply the propaganda needs of the armed minority.

A central problem is that loyalism is a narrow political ideology. It is at its core about defending Ulster with guns if necessary and as such does not have complex political positions on a wider range of political issues. The Good Friday Agreement was presented to unionists as evidence that the Union was safe. But, reassuring as that message may have seemed, to loyalists it was tantamount to telling them that their organisations were no longer needed to ‘protect the Union’. There is thus an element of existential angst in loyalism holding on tightly to its core message.

For all these reasons, loyalist muralists stuck to what they knew best, painting masked, armed men, even though with each passing year these images became increasingly anachronistic (see figure 7). While these murals may have reminded the faithful that, like the republicans, loyalists had their heroes, they did nothing to widen the palette of ideas or to reassure people that conflict transformation was worth the pain involved.

Figure 7. UVF gunman, Carrickfergus 2013

Figure 7. UVF gunman, Carrickfergus 2013

That said, there were some possible outlets for new representations. History is one, and so there have been depictions of Cromwell, the 1641 massacre of settlers by natives, and indeed King Billy from time to time. The history of the Ulster Scots emigrants to America and their descendants has also been an occasional source of mural inspiration, with murals depicting Davy Crockett, hero of the Alamo, as well as Andrew Johnson and Andrew Jackson, two of the 16 US presidents said to be of Ulster stock.

By far the greatest self-motivated changes have been in UVF controlled areas. The current UVF was formed in 1965 and as an act of homage was named after the original UVF, formed in 1913 to oppose Home Rule and disbanded in 1923. There is no direct connection between the two organisations. But that does not prevent the current UVF claiming the original organisation as its progenitor and to constantly reference World War I and the 36th Ulster Division which grew from the original UVF. What the current UVF has in fact done is replace murals of illegal armed men with murals of legal armed men (see figure 8). Despite the change, their murals continue to rest on a valorisation of violence.

Figure 8. Tribute to local British Army soldiers in World War I, Crebilly Road, Antrim 2018

Figure 8. Tribute to local British Army soldiers in World War I, Crebilly Road, Antrim 2018

Conclusion

For unionists, mural painting was for many years in effect a civic duty. They represented a pro-state demonstration of solidarity and loyalty as well as an affirmation of British identity. For republicanism, mural painting when it began was part of a sustained effort against containment by the state and other major institutions in society. Where the streets and the airwaves were dominated by unionism, murals became a way to pronounce one’s politics and identity unencumbered by control, marginalisation or censorship. The message was one of resistance to the state and to repression.

The fundamental change has been the commitment of republicans to peaceful and democratic means towards achieving their desired republic. That has led to alignments up until recently seen as impossible. Republicans maintain that this is not a betrayal; their agreement with the state is pragmatic. In addition, they maintain that in setting aside the military option they have a range of other strategies and techniques to achieve their goal, from elections to street protests. Within that range, murals continue to play a role. Despite the compromises and obstacles involved in the peace process there is room for vision and indignation, whether in memorials to dead comrades, recollections of key points in resistance, identification with struggles elsewhere in the world, or calls for justice in relation to past state repression (see figure 9).

Figure 9. Mural commemorating child victims of rubber and plastic bullets, Twinbrook, Dunmurry 2000

Figure 9. Mural commemorating child victims of rubber and plastic bullets, Twinbrook, Dunmurry 2000

The republican goal of the republic is in the future, and this future orientation can encourage hope, promise and aspiration. The loyalist affiliation to empire is much more problematic. For a start, the empire no longer exists. There is still, of course, the British Commonwealth; thus occasionally one will see references to, for example, Commonwealth troops in the British army in both World Wars. On the other hand, the Commonwealth is a mere ghost of empire. And empire, unlike the republic, is in the past. Figure 10 provides a clear example. The British monarch involved is not the current one, but her father. The ships and planes are Second World War vintage. The central figure, Britannia, is not one with whom it is likely that vast numbers of British people, the young and the newly migrated in particular, identify. The loyalist aspiration displayed here is for a world which no longer exists, if it ever did in this idealised fashion. Moreover, it is a retreat from the world in which they actually live, where unionist hegemony is severely wounded and conflict transformation is strongly touted as the new hegemony.

Figure 10. Britannia, King George IV and Queen Elizabeth, East Belfast 2004

Figure 10. Britannia, King George IV and Queen Elizabeth, East Belfast 2004