Murals

The Yorkshire Artists Mural group was set up in 1978 for practical co-operation among artists and to raise funds for projects. It included painters, potters, weavers, printers and sculptors and operated for five years. Its principal muralists were Graeme Willson and Ramsay Burt.

Graeme Willson

Graeme was born in North Yorkshire in 1951. His father was in the RAF and typically of service families, they moved peripatetically, round Europe and Britain. He recalls his boyhood being happy and pretty ordinary up to the age of ten, when in order to bring some stability to his education, Graeme was sent to boarding school. At about the same age on a holiday in Germany he was taken to the Kröller Müller museum and discovered Van Gogh. His paintings had a startling and profound effect. “That’s when I got the art bug,” he said, “the impact of Van Gogh and his almost missionary dedication to his work and the story of his life had such an enormous effect on me.”

childhood, and discovering Van Gogh

Boarding school had a formative effect. On the one hand, being sent away from his parents for six years to a place where the regime was hard and unfriendly and bullying rife had a deep emotional effect. On the other hand, he found friends, discovered strategies to cope and was greatly encouraged by an inspirational art teacher who taught him how to observe and draw precisely, and by his housemaster who found him an attic studio to escape to draw and paint in. “I was just exploring my personal and imaginative world through art” he said, “I was determined to be a practising artist – it has been my life-long goal.”

Graeme went on to sixth form at Leeds Modern School, passed three ‘A’ levels and an ‘S’ level. There was a career choice: he had grown up with a strong Christian faith and had considered studying to be a cleric, but chose art instead. In1969 he applied to do the Fine Art Course at Reading University, “to spread my wings and be nearer London,” and was accepted. It was not what he had expected. “The course was very avant garde, tutors all very decent people but none of them wanted to teach figurative art, rather to teach students to be experimental, conceptual and cutting edge. There was little teaching of traditional skills so I taught myself, going to galleries, studying the old masters and drawing from casts – we even had to campaign to get life drawing! In the end I did more art history than fine art for my degree.” Three times the art department went en masse to Europe. Italy particularly made a mark. “That for me was massively influential; my first experience of Italian fresco painting – it was like the Van Gogh experience – just knocked me out! I was bowled over by it, the bravura, the panache, just the way they covered the walls. It was that, combined with my becoming more left-wing, made me the public artist.”

on seeing Italian frescos

On leaving college in 1973 Graeme found employment teaching art in a technical college in Scunthorpe. After two years, still determined to paint full-time, he threw in the job and returned to Leeds, finding a flat to live in, and painted there full-time for five years, sounding out galleries and selling paintings. By 1978 he had also found a half-time lectureship at Bradford College of Art, teaching Art Practice and History.

the art into landscape award leads to new ideas

He also began work as a mural painter, commissioned to produce works for church interiors, which were well received. And he was becoming aware of the Mexican muralists and muralists around the UK. There followed a mural inspired by the city environment, the “Inner City Redevelopment Mural”. It raised questions about urban reconstruction – “Leeds was being sliced through by these great motorway structures, the disruption of old Victorian communities, so the scene alternates between concrete and dereliction/concrete and dereliction. The main artistic influence on me was Piero Della Francesca, his monumental frieze-like frescos.” This mural began as a maquette, exhibited at the Serpentine Gallery in 1977 for a Sheffield mural, depicting a riot in that city, for which Graeme won a national competition “Art Into Landscape”.

a social consciousness in the period of unrest

Declined for its subject matter by Sheffield Council, the design reappeared in a more confident, developed form in Leeds in 1978, funded by national and local arts grants. It was a massive mural, painted on marine plywood and painted in Ripolin (enamel paint), it stood out dramatically on supports from the ravaged central city wall. On it were painted, in trompe l’oeil, the buttresses of the ‘new development’ he invented forms, which seem to break into ‘our’ real space in front of the many figures of construction workers, dignitaries and people depicted in convincing realism. It was the first big mural to appear on the streets of Leeds, made a great impact, and lasted for twenty years – four times the life the artist expected. When it was attacked by the National Front in 1980, their fascist graffiti was cleaned off promptly by a council clean-up squad. Graeme says of himself: “I was an old-fashioned individualist; I would take into account the wishes of the community but I wanted to do the work myself with chosen assistants rather than any old member of the public; for me it was an issue of quality, being wary of endless jungles and child-like imagery.” Graeme employed assistants regularly and they worked well together. He says it was fun, he was able to work more efficiently and they learned from his teaching and the experience of working in a team, feeling the great scale and exhilaration of being up a scaffold.

Leeds -Liverpool canal mural

Shortly after this Leeds City Council established a public art programme, and commissioned Graeme to create a mural on a site by the Leeds-Liverpool canal. He prepared the work in models, detailing each of its elements, and squared up and drew the composite picture onto shaped plywood panels, picking up on the forms of lock gates, beams and bridges. It was called ‘Fragments From The Post Industrial State’ and its theme was the conflicts between dereliction of buildings and the decline of traditional industry versus engineering structures, modern industries and nuclear power. It stood out from the canal wall as a layered relief.

In 1983 the Greater London Council commissioned murals for railway stations and Graeme won the commission for Surbiton Station in South East London in collaboration with the artist Sue Ridge. He was to design and paint murals for the two side walls of the Station’s foyer and Sue would paint her mural directly onto the prepared ceiling. “It was a 1930’s building, in a shocking state of disrepair, ripe for some kind of public art,” he said. “On one side there were passengers, all ages, coming and going, leaning on railings, waiting, embracing and talking. On the other side were the railway workforce, union people, drivers, porters, labourers, ticket staff doing their stuff.”

the Surbiton murals

His pieces were painted on canvas in Leeds, transported down, adhered to plywood panels and installed by a community task force. Graeme’s trompe l’oeil architecture and figures made play between what was paint and what was real. Local people loved the murals, which were there for twenty years in pristine condition. Then, when Railtrack succeeded British Rail, without consultation or warning and on the pretext of redecorating the foyer, Sue’s ceiling was painted over and Graeme’s panels were torn down and thrown away. There was public outrage, but there was no apology or explanation. Convinced that politics were behind the destruction the vandalism hurts him still. “As a public artist you are very vulnerable, to the whims of fashion, changes in authority and power. It was a beautiful space. Now it looks as if it had been hit by the reformation. Stripped out. Bare.”

Graeme’s final outdoor mural, painted using the Keim system in 1990, was a commission for Leeds Corn Exchange. Called ‘Cornucopia’, it combines his interest in formal curves and angles, with his love of people and has a daring, dynamic effect on the building and environment. He also painted murals, textiles and stained glass for interiors of churches, and for Morrison’s Supermarkets produced richly coloured murals.

Graeme died in 2018 soon after he made recordings of his life and work for this project.

Ramsay Burt

Ramsay was born in May 1953 in Southport. His family was professional middle class – his father had been a dentist in the Royal Navy and his mother a WREN who had been in charge of and teaching a navy coding team. They were professional middle class but always lived in the north. Ramsay read a lot – at ten was reading John Buchan and Len Deighton, and drew incessantly, describing his drawings as “sort of doodles, usually of building, streets and cars”. He always had one or two good friends and remembers cycling to the beach, a special place with its sand hills, birds and the vast sea, it’s special light and the sunsets.

He was sent to boarding school at eight and after that, from thirteen to eighteen, to Shrewsbury School, getting a rich and diverse education, which offered all sorts of opportunities for indulging in the arts – including visits to London galleries. “I had a very wide cultural immersion by the time I went to art college.”

Shrewsbury and culture

From there he went to art school in Southport for a foundation year which was happily broad and experimental and which introduced him to underground and conceptual art. Going on to Leeds Art School in 1972 to study fine art, he found it was “a course which was much more disciplined, I learned to use oil paint properly, and we did lots of life drawing taught in the Coldstream method.” Lawrence Gowing was the head and there were well known lecturers, among them “John Elderfield, who was an expert on Greenbergian modernism and showed us slides, so we were getting loads of stuff; but I just wanted to paint in a representational way.” Of other tutors the painter Norman Stevens made a deep impression – Ramsay visited him in his studio, and Norman Adams, whose watercolours he admired, encouraged him to paint landscapes.

“Just after I graduated but was still around, a new group of lecturers, Marxist, feminist, situationist, took over in Fine Art and Art History at Leeds. There was a really interesting radical scene developing from 1976 to 79 that we were on the edges of, that included new wave punk groups, Leeds Animation Workshop, Leeds Postcards, Impact Theatre, Red Ladder, and the feminist ‘Pavilion Project’. I was hanging out with people, discussing ideas, helping with projects “not needing much to live on then, we had time to not do things and think, or to do things! I made lots of connections with community theatre and community dance, and somehow, with mural painting, and my trajectory as a mural painter would be from realistic painting to using realistic painting more in a community context. And that was the period when we started painting murals.”

an inspiring radical scene

After art school Ramsay taught part-time at Jacob Kramer School of Art during 1976-77 and I was invited by Graeme to co-teach history of art part-time at Bradford College of Art from 1978 till the late 1980’s. Ramsay was producing paintings for exhibitions with some success in 1966 and 77 whilst he was living in a terrace of back to back houses – now demolished – and painting lots of pictures of streets and gates and doorsteps, but not people. It was urban realism, with its structures and atmosphere, light and colour, owing something to Norman Stevens and Paul Nash.

the first mural

Graeme Willson invited Ramsay to join the Yorkshire Artists’ Mural Group in 1978. Ramsay found a site for his first mural on the edge of the John Kramer campus on a prominent wall by a main road, 50 feet long and 25 high. The brickwork was poor and it had buttresses, so he decided to paint the image on exterior plywood in good quality oil paint, aware that the vast size would push him to create an image of greater complexity. His work was speeded up by painting the boards pinned to the Grand Theatre’s giant manoeuvrable set-painting frame, assisted by art students and friends. The mural, called ‘Woodhouse Gates’, was of two semi-detached houses and their gates and based on his current themes. Northern Arts funded the mural and a grant from the local authority enabled the new murals group to buy a scaffold tower. Again with friends’ assistance Ramsay erected the panels onto battens bolted to the wall. The mural became a talking point in the city.

the response of the public and erecting the mural

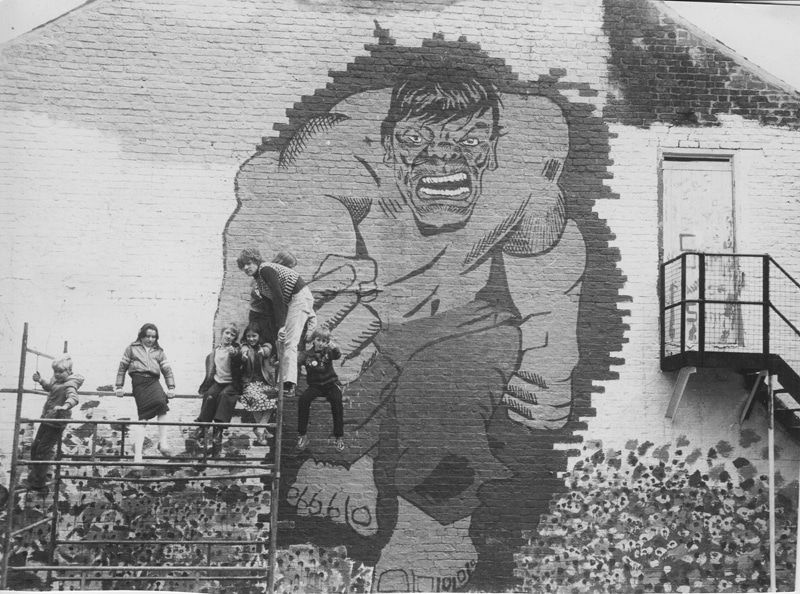

“I worked with a community project in Armley, which was next door to a theatre group called ‘Interplay’ that did projects in working class areas, painting a mural with children on the gable end of the Community Centre. It’s called ‘The Incredible Hulk’ and it shows him breaking out of the wall.” Ramsay likes this mural as a special moment in the opening up of his political consciousness. He says the mural is “one which to a certain extent one should be ashamed of, but I never was!” and recalls, “We put a nail in the wall, attached it to a string and did a perspective for all the bricks!”

‘Incredible Hulk’

After this Ramsay definitely got more interested in murals, and went on a tour of Wales and the North West photographing murals. He studied the report of a London conference to discover what other muralists were doing and what community-based practices there were, finding a position for himself amidst current ideas about community rights, funding, recognition, and the need for quality. Talking to Sandy Nairne about this he could not extract approval for his work. Was it that Nairne’s taste was too avant-garde or was it Thatcherite pressure on the Arts Council?

Ramsey created ‘Woodhouse Retrospectives’ next in a place where he lived in for seven years, it’s about history of the urban landscape.The location was a large breezeblock wall round a school playground.

Woodhouse Retrospectives

“We talked to everyone about what was there before: a church we discovered, a tram-line crossed the playground, there was a cinema nearby, and I painted all of these. Then collaged over this are three bits like 35mm slides, into which went images of the sort of paintings I was doing, working-class turn of the century back to back housing, gates, corner-shops, a map of the area and an image from the architect, of the school being built. Then the silhouette of the church coming through from behind, and finally, a key which said what it all was. So it was an image of urban change. I was juggling these elements like a big collage. Formally I was interested in how you put things on a wall that is relating to the architectural whole; the mass of the tram, the church, the shape of the old cinema and how it relates to the school when you see it from a distance and it goes round the corner with another image. Most of it was painted straight on the wall but when there was detail then it was painted onto shaped plywood, which was glued and screwed to the wall. I was working with local people and schoolchildren, if they asked me what am I doing I say, ‘Do you want to do a bit?’

Bermatofts

The final mural was the ‘History of the Bermatofts’ about the history of people and work there, with a pottery at the top and a brick factory. I had an idea for a Pollock’s Toy Theatre to go out from the front of the gable end – on a steel structure – of this sixties community centre. It sums up what I wanted to do, working with a community, finding imagery and assembling all these different elements, putting things on that relate to the shape and purpose of the building. Here I am working with the community and women helping me paint and kids and so on and feeling ‘well here is an artist working with the public and producing something they had a say in and have some ownership.’ ”