John created murals in Glasgow, Dundee and Glenrothes

He was born in 1948 in Dundee, his mother was from Angus in the hinterland of Dundee, her father was a farm labourer. She left school at fifteen to work in a jute mill in Kirriemuir, later becoming an auxiliary nurse during World War 2 looking after prisoners of war and met his father, a Polish soldier at a dance in Broughty Ferry. He was a tailor who later established his own business. When the family, with John and his sisters, moved to Aberfeldy, Perthshire, he recalls seeing films and cartoons at the cinema there, and playing in the woods and moors, and at home, drawing, painting and making plasticine models; fabricating his own imaginary, independent world. The family moved to Glasgow when he was seven, He remembers becoming aware of the social divisions created by religion, nationality and class, aware too of the brutal redevelopment in the city, of gang culture, and of himself being an outsider – from the central Highlands and east of Scotland.

He often found school “useless and confining”; there was use of leather straps for punishments and at times an atmosphere of intimidation. His primary interest was art, and John recalls the excellent art teachers who taught and encouraged him at secondary school. He would spend evenings and weekends finding places to paint at the docks or the countryside outside Glasgow and attended a Summer art camp, winning prizes. At the age of fifteen his art teacher agreed he should aim for art school, and two years later in 1966 he entered Glasgow School of Art (GSA).

John’s first year of the ‘General Course’ was a time of discovery, reading Gombrich, arts magazines, and achieving success in GSA’s conventional terms. As well as getting acquainted with the specialisms of graphics, sculpture, industrial design and textiles, he was discovering a range of contemporary arts movements. In summer 1967 he hitch-hiked to West Germany, drawing, painting – exploring ideas with German artists and students – and becoming interested in art forms like Dada, Surrealism and abstraction, and current movements like Pop, Land Art, and Performance.

Dada, Fluxus, Land Art? – the art school stuck the past

He came to realise that within the art school, an over-reliance on traditional methods of teaching had made the fine art departments impervious to change, and that abstraction and experimentation were vilified. He visited arts events in Edinburgh, and London, Dublin and Europe, making contact with a wider cultural world. In 1969 he exhibited a large 3-D multi-media work in the Scottish Young Contemporaries Exhibition (SYC) in Edinburgh’s Richard Demarco Gallery, becoming a prizewinner. “In Scotland,” he said, “there was no other venue for contemporary art beyond the Demarco Gallery.”

John’s SYC exhibits in Edinburgh and London

When, at the end of that term, the Drawing and Painting Department failed his year’s work, he found refuge in the Sculpture Department, but was then in a serious car crash. After recovering, he made works for several exhibitions, and in mid-1971 took the lead role in designing and constructing a Pop Art bar in Glasgow, named “The Muscular Arms”. He never resumed his GSA studies. That bar’s startling success lead to further commissions. In 1972 he founded his company Artifactory (GLW) Ltd., designing for clubs, bars, restaurants and shops, doing graphic illustration, set design and making exhibition and events environments, mostly in Scotland, in the following years.

wall artworks in the Muscular Arms bar in Glasgow

By 1977 Artifactory was about to voluntarily close. John had become increasingly concerned with wider political and environmental issues at home and abroad, and with changes to his immediate locality. Glasgow’s 1960 civic planning for Garnethill, where he had come to live, had condemned much of its tenement housing to be demolished over the next 20 years. By the mid-seventies, growing dereliction lead to determined public resistance. John was on the Garnethill Local Plan Working Party which eventually reversed these planning zonings, permitting reinvestment and repair of the tenement housing. He was instrumental in starting the Garnethill Community Council, and co-wrote it’s 1975 constitution.

At ‘The Garnethill Exhibition’ (in the city’s major arts venue, the Third Eye Centre), which he organised with Tom McGrath and Garnethill residents in 1976, there were exhibitions, performances, events and shows involving schools, colleges, professional performers, museum displays and contributions from communities across the city: also architectural studies, video projects, photography shows, self-publishing and embroidery demonstrations. An estimated seventeen thousand people attended.

resistance to the city’s plan for Garnethill in 1970s

In 1977 John proposed a scheme of murals and environmental improvements for Garnethill with the Community Council. There were indications that projects to employ adults and young people could be funded  by Manpower Services Commission. “Initially we decided to create two murals, one mosaic, one painted. With a promise of a guarantee against loss from the Scottish Arts Council (SAC) and a matching sum from the Scottish Development Agency (SDA) for environmental improvements, we had our core funding! Aspects of the project were going to be very expensive so were lucky to come across companies around Glasgow with redundant boxes of glass and ceramic mosaics which they donated, and we negotiated our paints and scaffolding and other equipment at reduced price.”

by Manpower Services Commission. “Initially we decided to create two murals, one mosaic, one painted. With a promise of a guarantee against loss from the Scottish Arts Council (SAC) and a matching sum from the Scottish Development Agency (SDA) for environmental improvements, we had our core funding! Aspects of the project were going to be very expensive so were lucky to come across companies around Glasgow with redundant boxes of glass and ceramic mosaics which they donated, and we negotiated our paints and scaffolding and other equipment at reduced price.”

Another gable end wall was added to the scheme and each wall had to be repaired and rendered before John could begin the painting. As director of the project he brought in his artist partner from Artifactory, Irene Keenan, to help manage the grants and payments to artists.

Garnethill murals – project scale and funding

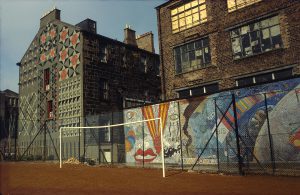

Two of the walls overlooked vacant ground that was to become a park, the long wall for the mosaic image, and the other, a typical Glasgow tenement gable end, would have a design selected by competition. The proposals and objectives had been written up during the project development stage, including a stipulation that there should be consultation within the locality; an account was set up with the Community Council. For the first painted gable mural, the artists exhibited their designs in the Community Shop on Hill Street; everyone could cast their vote. The winning design, a geometric pattern, was by the local Garnethill artist, Tommy Lydon.

“The site for the mosaic mural was a wall forty feet long by twelve feet high. The ground in front of it – what was to become the community park – was a rough clinker waste-ground, which we persuaded the city to level and landscape, creating a play area and football pitch for local children, establishing the first Garnethill Park. The mosaic design arose from holding children’s art classes managed by project artists, held regularly in the evenings in the Community Shop. Dozens of children took part. It was quite different from art at school – for here the space was theirs. From the great many paintings and drawings that were produced we selected a smaller number and then had to find a way to resolve them into one entity. We thought with it’s characteristic of childlikeness, interpreting their work in glass and ceramic would be a very expressive way to present it.”

“The site for the mosaic mural was a wall forty feet long by twelve feet high. The ground in front of it – what was to become the community park – was a rough clinker waste-ground, which we persuaded the city to level and landscape, creating a play area and football pitch for local children, establishing the first Garnethill Park. The mosaic design arose from holding children’s art classes managed by project artists, held regularly in the evenings in the Community Shop. Dozens of children took part. It was quite different from art at school – for here the space was theirs. From the great many paintings and drawings that were produced we selected a smaller number and then had to find a way to resolve them into one entity. We thought with it’s characteristic of childlikeness, interpreting their work in glass and ceramic would be a very expressive way to present it.”

The mosaic components of the mural were each fabricated off-site, on large damp sand beds, which held the mosaic pieces firm until scrim fabric was glued onto them, and the entire panel of mosaics could then be cut into smaller sections which were numbered and plotted on a plan. Then rather like a huge jigsaw, the hundreds of sections were cemented on the wall by the project team, assisted by the youth workers. It was finished in the Spring of 1979.

The third mural gable wall was scaffolded and cement rendered, but with the project running out of funds, it was designed by John, taking account of his awareness of local demands, and painted with artist assistants,

“The theme of my mural was heaven and earth, its form was a series of interlocking grids that would allow a speculative understanding of the meaning of ‘Garnethill.’ On the right, the ‘heaven’ side, is a vertical poem of words set in pairs, where the words constitute progressing sequences. From the top, ETHEREAL COSMOS, descending through, ASTRAL GALAXY, STAR CLUSTER, EARTH MASS, and STONE MOUNT, then GARNET HILL, and continuing in that way to ICE AGE at the foot. On the left side the ‘earth’ theme complements and completes it.” The idea was he says, “Primarily to protect the buildings, the history of the area and the community. Our interventions began to ring! First thing: stop the demolition, to allow time for consideration, so investigation and better knowledge could evolve.”

“The theme of my mural was heaven and earth, its form was a series of interlocking grids that would allow a speculative understanding of the meaning of ‘Garnethill.’ On the right, the ‘heaven’ side, is a vertical poem of words set in pairs, where the words constitute progressing sequences. From the top, ETHEREAL COSMOS, descending through, ASTRAL GALAXY, STAR CLUSTER, EARTH MASS, and STONE MOUNT, then GARNET HILL, and continuing in that way to ICE AGE at the foot. On the left side the ‘earth’ theme complements and completes it.” The idea was he says, “Primarily to protect the buildings, the history of the area and the community. Our interventions began to ring! First thing: stop the demolition, to allow time for consideration, so investigation and better knowledge could evolve.”

Then in the Summer there was a Garnethill “Festival Day”, a celebration with all the different groups in the community. With a procession, music and theatrical performances, martial arts displays, floats and stalls, a grand opening of the park. There were blessings of the painted murals and mosaics from different religions, and a dedication to International Year of the Child.

the opening of the murals and 1979 park

In the early 1980s John was commissioned to create a mural for the Wellgate Library in Dundee. Though delayed several years, it was completed in 1987. The work addressing the Tay Bridge disaster of 1879, was more than forty feet long with a rusted frame structure, painted images behind. The image sources included an ancient Celtic stone, Michaelangelo’s depiction of Jeremiah, storm scenes and Islamic patterns, metaphors for man’s lost ability to work with the forces of nature. “Our systemisation heralds breakdown” he says.

In the early 1980s John was commissioned to create a mural for the Wellgate Library in Dundee. Though delayed several years, it was completed in 1987. The work addressing the Tay Bridge disaster of 1879, was more than forty feet long with a rusted frame structure, painted images behind. The image sources included an ancient Celtic stone, Michaelangelo’s depiction of Jeremiah, storm scenes and Islamic patterns, metaphors for man’s lost ability to work with the forces of nature. “Our systemisation heralds breakdown” he says.

In 1992 John was commissioned to paint a seventy foot long underpass in Glenrothes in Fife. The main subject was a much mythologised Scottish figure from the Middle Ages called Michael Scot, known in the literary centres of 13th Century Europe, as far as Palermo and the court of Frederick II. Scot was a mysterious and controversial scholar, writer and translator, and his achievements are only now being better understood. Legend associates him with Balwearie, not far from Glenrothes.

People were intrigued by his images, and talked with John and his assistants as they worked, and gradually came to accept them. More people began to use the underpass, which encouraged him, “but at the outset everyone said, “You’re wasting your time.” They battled through a harsh Spring for three months to complete the scheme, noting that at least whilst they were there the murals came through unscathed. “The concept of arts in the community,” he says, “is that you are not alone!”

People were intrigued by his images, and talked with John and his assistants as they worked, and gradually came to accept them. More people began to use the underpass, which encouraged him, “but at the outset everyone said, “You’re wasting your time.” They battled through a harsh Spring for three months to complete the scheme, noting that at least whilst they were there the murals came through unscathed. “The concept of arts in the community,” he says, “is that you are not alone!”

Text by Steve Lobb & John Kraska