Louise Vines set up the mural group ‘Brass Tacks” in 1982 and organised the womens’ mural co-operative ‘London Wall’ in 1983 together with Maggie Clyde, Susan Elliot and Sonia Martin.

Louise was born in London in 1957. Her father and mother met at a Jewish ex-service men’s dance in 1947 and she had an older brother and sister. Her father was an active communist until Stalin was denounced. They supported left-wing causes and Louise took up the women’s movement slogan of the sixties: ‘The Political is Personal’. Louise went on CND marches from the age of three, “part of our life. I always saw it as a normal thing to do, to make my voice heard and not to accept the status quo, the way I was brought up.” Her mother was a flower arranger and made a beautiful garden. Father was a storyteller, he made up stories about Italian children on their walks together.

school

Louise loved her school, a free school created by Bertrand Russell. She was there from age five to eighteen and had very good friends, “it was my home in those days – a very happy place to be – teachers on first name terms – small classes and wonderful art teacher who encouraged me to draw and paint.” Dancing, art and literature were her great loves. At eighteen she chose to study Art – over English and in 1975 went Camberwell Art School for a foundation year and afterwards studied there on the degree course in painting, making pictures of her father’s factory. “I wanted to be out there in society and not just in the cloistered walls of the art school. I got very active in the Anti – Nazi League and went on marches all alone, I couldn’t get anyone interested – artists were in their ivory towers in those years. I made a painting about a march through Lewisham and I was quite frightened by how much violence I felt towards the National Front. The painting was shown in Clapham Gallery ; after the Gallery was threatened they had to take it down – I was quite pleased about that.”

marching in Lewisham and seeing Royal Oak murals

Louise went on to a post-graduate painting course at the Royal Academy Schools (RAS) from 1979 to 1982, where she won awards, including a commission for a mural. She was walked around London researching murals, “they were starting to pop up all over the place,” and in the mid -1970s saw the Royal Oak Murals . “I was thrilled to find visual artists working outside the gallery.”

Two weeks after leaving the RAS Louise was asked to I set up a mural group as part of “Brass Tacks” – a Manpower Services Commission project to get young people off the dole. “I found a number people signing on as ‘artists’ and the first mural we made was “Over Water Under Water” at the Angel Road Nursery in Brixton. We didn’t get much money but we had a job! It was amazing!

Everyone had a different way of painting so how were we to unite us to design together? I was keen on Matisse and his cut outs so I decided we would cut out the design from coloured pieces of paper so that the scissors would impose a style on us, and it worked! From then on our murals were very cohesive.” Brass Tacks Mural Group painted a lot of murals, with youth groups, with community groups on estates and in schools across South London. “When we did individual murals we might abandon the scissors-style imposed on the group, though the colour was still influenced by the painted paper. I was influenced by the American, Agnes Martin, who did a series of paintings in shades of grey.”

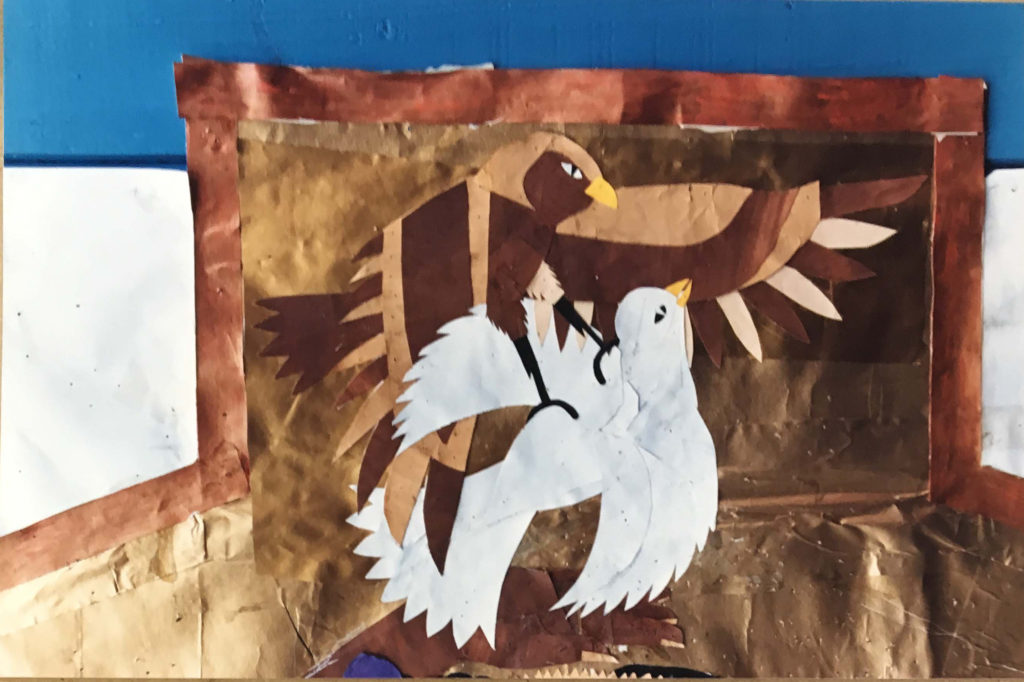

finding a wall for The Womens’ Peace Mural : The Sankofa Bird

“After a year I got the urge to be independent, so I talked to the people in the group who most appealed to me – and they were all women – and suggested we set up a women’s mural group – Maggie Clyde, Susan Elliot, Sonia Martin and me – Sonia suggested we call it London Wall; we set it up as a cooperative and registered charity. The Peace Murals were getting going, with funding from the Greater London Council (GLC) so we went to the GLC, actually marched in to Tony Banks’ office. I was in awe of authority in those years so Maggie did the talking. We said, “you need a women’s peace mural”, which he agreed, and we got the money.’” They found a studio in Brixton with other local groups and looked for a wall. “Our first choice was a wall facing the Imperial War Museum, then a journalist phoned me up from the Sun newspaper, and they put out a story saying raving lesbians were getting money from the GLC. Eventually we found the site on Pentonville Road but we had to keep it quiet because – following the Sun story – the head of the organisation that we were associated with did not want it to be known that it was us in case he lost his funding.

putting the design on the wall

The theme of ‘The Sankofa Bird’ was Maggie’s idea. It is a symbol from the Akan people of Ghana: the Sankofa Bird looks backwards into the past to make a better future. We all liked the symbol, which is central to the mural. We designed the mural using the cut-out paper method. It was the first mural we painted in Keim. To protect us from threats against the ‘disgusting women’s mural’ our scaffolding was covered in blue plastic sheeting so we could not be seen while painting. Our process was to photograph the design, print it as an A1 photograph for each of us and square it up. We gridded the wall with a chalk line and transferred the design onto the wall. Then painted by numbers. I loved pinging the chalk line, it was like magic! Pinging! I thought of all the frescoes I’d seen done this way in Italy, and the Mexican murals in books. Matisse was the main influence on style; the Mexicans were the inspiration for working in public places. At the opening there was a crowd and quite a party because we’d had a lot of bad press – from the Sun and the Telegraph – that’s when I realised all news is good news because all the press was positive – the press completely turned around.”

After Sankofa Bird, Maggie and Susan left the group. Sonia and Louise continued, often painting murals as individuals until 1992.

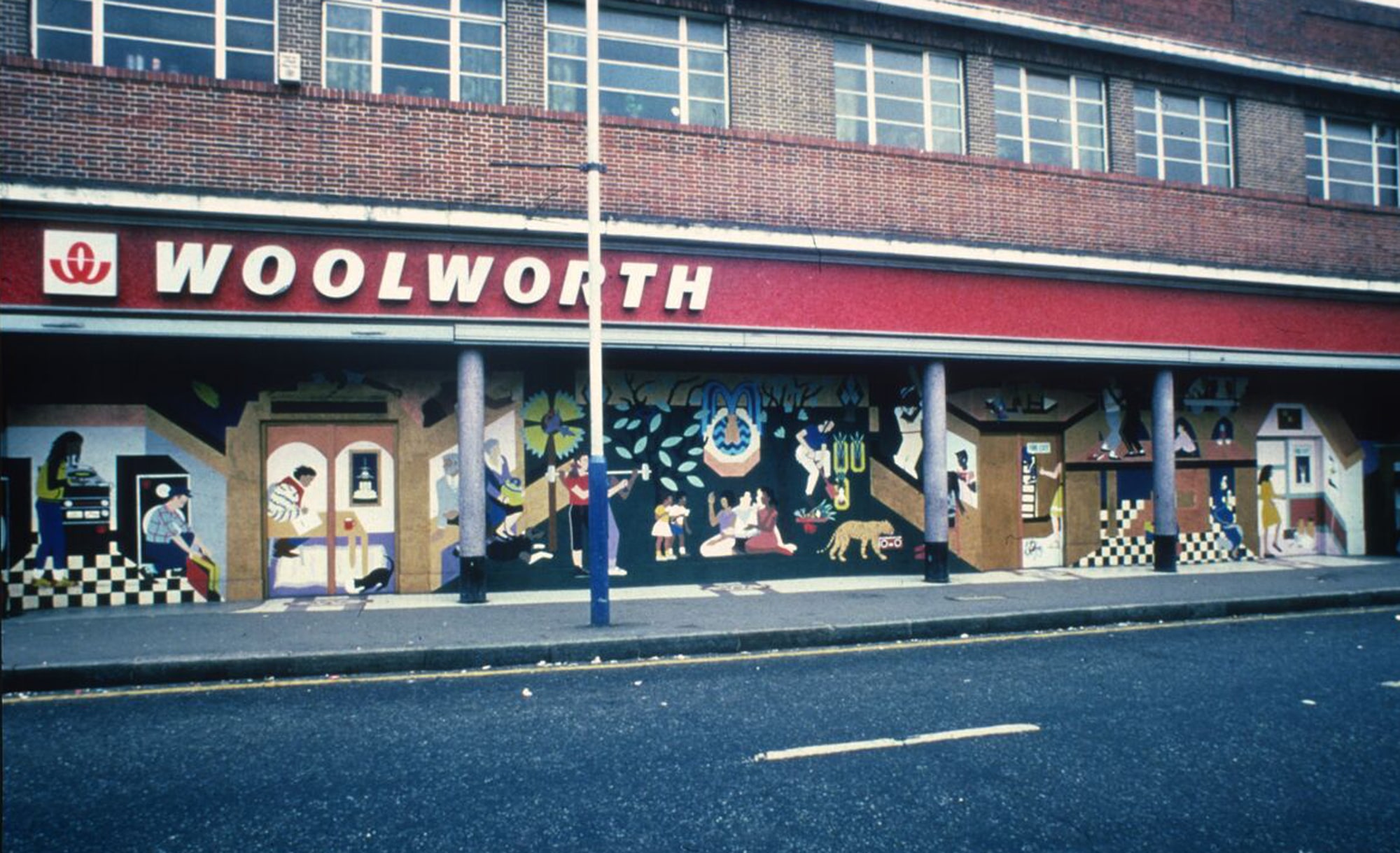

“In our work the responsibility I felt was to produce a mural in the best materials and after that it has a natural life. When we painted the mural on the side of Woolworths in 1982, the local anarchists decided to spray graffiti all over it and harangued us – very angry – we talked to them – cleaned it up straight away and because we talked with them together it didn’t happen again. And that’s the sort of responsibility I feel – when we were painting in East London there was an intifada going on and boys started throwing stones at us and I thought blimey! There are two things I can do: run away and not come back or talk to them. I told them they were great boys but they had to stop throwing stones – and they did. I feel a responsibility to the community when I’m doing it.

community and conflict

After us some muralists plonked art into public spaces with their view of the world without any consideration of the place and population – sometimes it works but sometimes I think its horrible. Art in public has to be part of that place and population. On the North Peckham Estate, riots were going on at the time I painted my mural in the Dachwyng Family Centre. The mural was about the centre and the people using it. I think the murals were the best period of my art – not that it was all great art but that it was connected to the community and to other artists and there was nothing I liked better than climbing up a scaffolding – it was a very buoyant period for art. Shelley said that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of mankind. I think artists are too. Think of ‘Guernica’ – that had an impact and the Mexican muralists had an impact. I don’t know if we did but we brought art into the public domain and to people who had never been inside a gallery – and that was my job.

the best period