Paul Butler was involved in the creation, repair and restoration of a number of major mural projects in London as well as many smaller community murals.

Paul was born in Bristol in 1947. He describes his family as ‘posh but poor’. His early memories are of ‘good bits’ but it was in some respects an ‘awful childhood’ because of his chronic and severe asthma and eczema.

being poor and art books

He has intense early memories of the illustrations in the Fairy Stories his father read to him and his little sister. Encouraged by his father he became an obsessive drawer and learned to love perspective, invented stuff, made cartoons and models of ships aircraft and houses of matches and balsa. He learned from books of Van Gogh and Vermeer that he won in art competitions, and he copied the drawings of Leonardo, “a conceptual drawer with such feeling for humanity”.

At eighteen he did a Pre-Diploma course at the art college in Bristol where he received a traditional grounding in etching, litho and silkscreen, drawing, painting, modelling, casting and carving. He then spent two years working on building sites, in an office and as a ‘beach-boy’ in Tenby – where his mother’s family came from – before being accepted by Kingston School of Art on the Sculpture and Drawing course, where he became “immersed in Modernism.” He recalls the clash of cultures between the full-time traditionalist teachers and the younger part-timers, the influence of American sculptors, seeing the work of Caro and Carl Andre, Marini and Giacometti, and in his own work moving from traditional modelling, casting and forging towards formalism.

Leaving art school, he got a studio in Brentford and took casual jobs, amongst them roadying for bands and stage shows. Then in Portugal, memories of childhood trauma, family bereavement, too much dope and depression caught up with him. “Totally borassic” and desperate he survived two months hand to mouth selling drawings. It was his turning point. Back home he worked on props and sets for the Royal Shakespeare Company for two years. Then sometime in the mid-seventies he woke up one morning and began to draw vigorously and large. He felt sick of the art business that only spoke to the ‘cognoscenti’ and he wanted his art to talk to people, to touch them emotionally. In 1977 he began to show his new work and became highly regarded.

a change of direction

After this Paul lectured and taught, had an Arts Council residency at Maltby Colliery in South Yorkshire, and many large public exhibitions. About 1978 knowing of their work at Royal Oak he wrote to Des Rochford and David Binnington saying he was interested in getting into mural painting. Sometime later David invited him down to Whitechapel where he had been researching the Cable Street project for two years. He was at this point drawing up and starting to paint the mural, and asked Paul to become part of the project, by designing predella panels for the foot of the work. He had only just begun when he got a call to say the mural had been extensively and brutally vandalised. On site, David explained he was physically and emotionally exhausted and could not go on, could not be persuaded to stay and left.

the artists prepare the mural again

Paul, “left holding the baby” called up Desmond Rochfort and Ray Walker and together they took over the project. The wall was grit-blasted to remove the damage, then reprimed and squared up again. Then, negotiating and working collectively, they researched images and redesigned the lower two-thirds of the mural, trying to retain the vertiginous perspective and twisting movement of Dave’s design whilst increasing the size of the images “…to make the images interlock, tight up to the picture plane.”

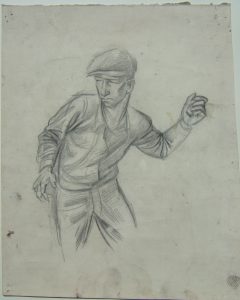

Ray took the left side, Paul the centre and Desmond the right side. Each artist did his own research. For Paul the key was the figure throwing a stone that he found in a tiny image in a photograph of the actual battle-scene. He took elements from David’s design, re-drew and formalised them, locked in diagonals. “It was a steep learning curve for all of us.” They talked through how to bring their designs together. He says he was in awe of Ray’s huge ability and notes that Desmond’s side is arabesquy, dynamic, like a Sequeiros. The mural had a great reception when it was opened in 1983

Ray took the left side, Paul the centre and Desmond the right side. Each artist did his own research. For Paul the key was the figure throwing a stone that he found in a tiny image in a photograph of the actual battle-scene. He took elements from David’s design, re-drew and formalised them, locked in diagonals. “It was a steep learning curve for all of us.” They talked through how to bring their designs together. He says he was in awe of Ray’s huge ability and notes that Desmond’s side is arabesquy, dynamic, like a Sequeiros. The mural had a great reception when it was opened in 1983

Since then it has been attacked three times by racists, and Paul has repainted it each time, in a very vulnerable position working of scaffold towers thirty feet high. In 1996 his car was doused in paint, its tires slashed and he received death threats by militant fascists.

death threat

After the Cable Street mural was completed Paul was appointed Artist in Residence in Hounslow and created two community murals both with young people, one at Redlees and a second one with kids at a Youth Centre on Convent Way Estate, to the West of the Borough. The mural – of breakdancers – was painted with gloss paints. Paul invited Bryn a famous breakdancer and graffitist on a visit from New Jersey to come and work with them, and also introduced him to the posh students at Oxford’s Ruskin School of Drawing where he did a series of dynamic graffiti style works on large boards.

In 1985 Paul formed an artists’ cooperative to renovate the “Small Mansion” building to establish an Arts Centre for the Borough which lasted for twenty years, hosted a hundred and fifty exhibitions, creating an arts education programme which offered accreditation for Thames Valley University courses.

The Greater London Council (GLC) declared 1983 to be ‘ Peace Year ‘ and among its awards gave £40,000 to the ‘London Muralists for Peace Collective’, a group headed up by Brian Barnes that included Paul, Ray Walker, Greenwich Mural Workshop – Carol Kenna and Stephen Lobb, the Brixton Muralists Dale McCrea and Pauline Harding who would each paint peace murals during the year.

The Greater London Council (GLC) declared 1983 to be “Peace Year” and among its awards gave £40,000 to “London Muralists for Peace Collective”, a group headed up by Brian Barnes that included Paul, Ray Walker, Greenwich Mural Workshop, the Brixton Muralists, Dale McCrea and Pauline Harding and the women’s group London Wall, who would each paint peace murals during the year. Paul recalls, “I got this wall in Shepherds Bush which was a hundred and forty feet long and fifteen feet high on the side of a telephone exchange on the Uxbridge Road and made of concrete panels. I fixed a framework and fitted expanded metal screens over it, then scrimmed and rendered it to the Keim formula. The design was complex, with all sorts of motifs relating to a mobius strip. It ran all the way along the wall in an extended figure of eight over a long shallow curve beneath, representing the earth’s landmasses, and a big satellite – referring to telecommunications. At one end was a radio transmitter dish and at the other someone at a computer screen. In the centre I painted an image of a newborn baby being christened and the water pouring down. The right-hand part was about of death and war with First World War images and the Hiroshima monument building that remains standing. At the other end are references to Buddist children dancing and Stonehenge. So it is quite complicated, a weaving together of all sorts of ideas. I painted it in a very low key arrangement of subtle greens and greys.” It was opened in 1984.

The Greater London Council (GLC) declared 1983 to be “Peace Year” and among its awards gave £40,000 to “London Muralists for Peace Collective”, a group headed up by Brian Barnes that included Paul, Ray Walker, Greenwich Mural Workshop, the Brixton Muralists, Dale McCrea and Pauline Harding and the women’s group London Wall, who would each paint peace murals during the year. Paul recalls, “I got this wall in Shepherds Bush which was a hundred and forty feet long and fifteen feet high on the side of a telephone exchange on the Uxbridge Road and made of concrete panels. I fixed a framework and fitted expanded metal screens over it, then scrimmed and rendered it to the Keim formula. The design was complex, with all sorts of motifs relating to a mobius strip. It ran all the way along the wall in an extended figure of eight over a long shallow curve beneath, representing the earth’s landmasses, and a big satellite – referring to telecommunications. At one end was a radio transmitter dish and at the other someone at a computer screen. In the centre I painted an image of a newborn baby being christened and the water pouring down. The right-hand part was about of death and war with First World War images and the Hiroshima monument building that remains standing. At the other end are references to Buddist children dancing and Stonehenge. So it is quite complicated, a weaving together of all sorts of ideas. I painted it in a very low key arrangement of subtle greens and greys.” It was opened in 1984.

In 1985 Desmond and Paul made preliminary designs for a mural of Labour History, and carried out the commission, inside the Labour Education Centre. It was difficult work: painting in acrylics, in an extremely hot interior and with the sodium lights, which meant they could not see the colours correctly. They were not entirely happy with the mural because of the disparity between their different styles, though Paul says,“it did the job, about Labour History – Tolpuddle and cotton workers and so on.” About the same time he worked with Peter Kennard at the Small Mansion on a Trade Union banner for Unison, a first banner for them both – “it came out alright.”

Paul says there is a stronger connection between the Left and art in Italy, Germany and France, but that the British art world suffers from a residual sometimes hidden, elitism. Many people still see art as being done by posh people for posh people. “A lot of British artists come from backgrounds where they are supported by money, there’s an awful lot of them. And there still is prejudice against leftist practice. I was exhibiting all over the place, but when I started painting murals it brought my career as a showing artist to a grinding standstill – partly because I was too stretched – but also because I was labelled a socialist realist”. He says many in the art business – gallerists and curators – are contemptuous of mural painting; that there is an internal dialogue within contemporary art practice where the cognoscenti are only talking to one another.

“I think that artists should be able to adapt to different environments and conditions and commissions and contexts. I have really enjoyed moving from being an easel painter to a muralist to an artist in residence to being a curator – I love that.”

responding to “murals are municipal art”

We should recognise that art should be accessible, commissioned for a public space for the people by the people. People say the harder you work the luckier you get – I’ve certainly worked hard – but I was lucky to get involved with the Cable Street mural, its been an absolutely wonderful connection and I am still connected to the East End and Jewish East End culture because of Cable Street, that’s an achievement I guess.”