Tim Chalk and Paul Grime founded ‘Artist’s Collective’ with David Wilkinson in 1981, before working together as ‘Street Artworks’ (1984 – 1988) and then as ‘Chalk & Grime’ (1988 – 1994), making murals and other environmental artworks in Scotland and the UK.

Tim was born in 1955, the third child of four in a middle-class family that lived in a terraced house in Hillhead in Glasgow, where there was always drawing and where in the back lanes and bomb sites the children would play. His parents were from Devon, his father taught classics at Glasgow University and always kept a sketchbook with him, and his ‘reasonable and reflective’ activist mother, was driven by concern for social justice and children’s issues.

He remarks on the difference between home and the back-lane Glaswegian world, “I come from the English ghetto in Glasgow, middle class but financially stressed.” At home he and his two elder sisters were always drawing, there were art books, ‘Studio’ magazines and visits to galleries and he made models of imaginary buildings. School was less encouraging; there were set rules and he got the belt for ‘starting his painting early.’ “There was no room for exploration, you were taught to believe ‘this is how it is.’” But by the time he was in the sixth form he was always in the art room painting and he discovered clay modelling and the techniques of photography.

art colleges in transition

Tim was accepted for a five year fine art course at Edinburgh University split between the academic Humanities’ study of Art History, and the Art College, training in drawing and painting. In Art History he was absorbed in investigating ideas, which had a critical stimulating effect on his future work, “intellectually rigorous, full of hard impartial research.” But the art college “was disappointing, directionless and in limbo.” During the Art History course the University offered travel bursaries and Tim was able to explore Renaissance art in Florence, Sienna, Assisi, Urbino and Venice. “I was stunned by the whole art scene,” he said, “it was a notional ideal, a socially engaged art.”

how do you escape from making trinkets for rich people?

In 1979, his course completed, Tim was selling shoes for two days and painting watercolours with enthusiasm the rest of the week. “But workwise, I was completely lost. I had discovered the existence of this thing called community art, and every Monday got the Guardian and looked at posts being advertised. It was then I clocked it and got excited.” At first the excitement “was at a personal theoretical level, it was only later by getting involved and engaged in it that the corners got knocked off and you learned how real people live and how valuable your art is – or isn’t – effective, valuable, creative and all the rest of it.”

He was applying for community artist jobs without success. Then by chance he had a call from Bob Palmer, director of the ‘Theatre Workshop Community Arts Centre’ in Edinburgh, and spent three weeks painting scenery for their Christmas show. He continued working with the company on temporary contracts for a year, touring on community events and play schemes and making sets and constructions, after which he was taken on full-time. “There was the teaching, learning, real-life experience that the University and all the rest of it had never given me. Those were my education years.”

theatre workshop

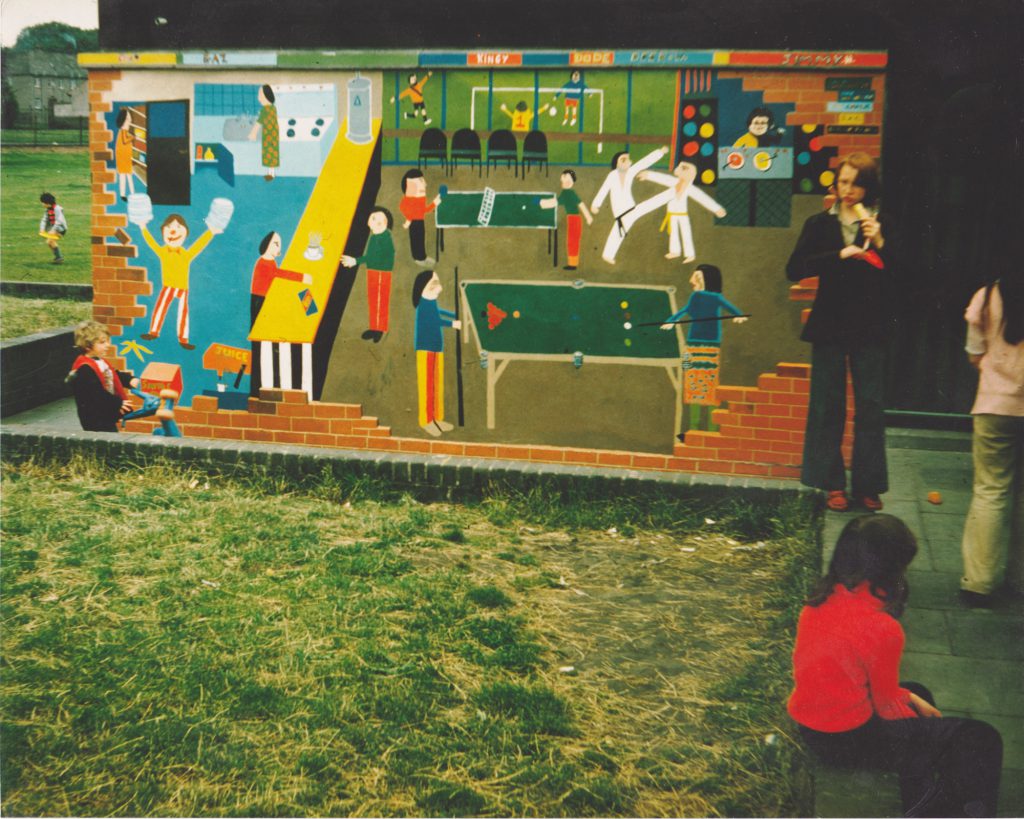

Tim’s first mural project was for the front wall of the Pilton Community Centre in Edinburgh. It came as part of a package of creative entertainments and activities ‘Theatre Workshop’ was providing for Pilton’s Annual Gala. Tim worked with children. Started with everyone making drawings of all the activities in the Centre. From all these he made a composition, combining their drawings, and took it back to the children for approval. They made the changes they wanted and the design was squared up and chalked on the wall. Tim outlined their drawings in black paint and for the next week through the mayhem of excitement and action, mixed the colours and directed the children where to paint – and tidied up the images afterwards so that their ideas were shown to best effect. “It was the first chance I had to put into practice all this theory that’d been kicking around in my head. And I had seen what worked and got the feeling the enthusiasm of all this group of kids. It was great!”

first mural

In 1981 a new director took over Theatre Workshop who was much more theatre-based. “Although he was supportive of what I and my visual art co-worker, Paul Grime, were doing, we saw that murals and environmental art were going against the mainstream. So we decided to leave and go freelance and set up our own company, ‘Artists’ Collective’. If we’d had a mission statement at the time it would have been ‘To produce high quality environmental art-work and to set up a model for artists working in the social context.’”

Paul was born in Stockport and grew up in a Newcastle-Under-Lyne where his father was a hard-working doctor. Early in his childhood the family moved to a home built for them on the edge of town, where he’d play on the building sites and cycle in the countryside. His mother was an artist and teacher so there was always art and constructing things going on with his elder brother and two younger sisters, in craftwork, clay and plaster. Paul recalls good times on Scottish holidays with his grandparents, who kept an old lifeboat at Oban. They moved to rural Banffshire when Paul was thirteen, and the brothers went from an uninspiring all-boys high school to a new mixed gender comprehensive school, better resourced and more exciting, where Paul enjoyed art, especially under a teacher who set exploratory assignments that “made you see things differently.” He read a lot of science fiction, novels and poetry and enjoyed walking on the high cliffs.

working up a good portfolio for art school

Paul went straight to Edinburgh Art School aged seventeen in 1973. There was a general design year that he enjoyed. “The social life was as good as I’d expected.” He made friends and enjoyed doing a range of creative activities, including exploring abstract images. His enthusiasm was rewarded when a tutor described him as a star student. Paul opted for drawing and painting for his main subject on the degree course. Besides the compulsory studies of the nude he began to do figurative work together with elements of landscape and pop imagery, and in his fourth year was painting images of the docks. After the degree show he stayed on for a post-graduate year. He was influenced by his friend Jim Mooney, a very good artist, very determined and a member of the communist party. “Edinburgh was a conservative place” says Paul. “It encouraged introspection. If you wanted to produce something not using paint it was frowned on.”

artistic conservatism and being of the left

Paul left the School in 1977 knowing that he would not be taking the usual route of teaching. He had discovered the work of the Mexican mural artists and had been thinking about the possibility of becoming a muralist and with an ‘Andrew Grant Scholarship’ he toured London to visit community murals projects.

the visit to see murals

He was encouraged by his girl-friend’s sister, Liz Kemp to work for ‘The Craigmillar Festival Society’ (CFS) where there were community initiatives and opportunities for artists. He began working with youth opportunities trainees making mosaics and painting bus shelters. His first significant mural was for the Jack Kane Centre, created with a young lad, Brian Haliday, a very questioning fellow and a karate black belt, with skills in drawing cartoons and vignettes. It was a very significant piece of work, being of large scale, rooted in the community, about a community taking control of its building.

For the next project the United States mosaicist Pedro Silva was invited to work with the CFS in Bingham – a housing scheme close to Craigmillar – to teach his skill and create mosaic with the community, assisted by Paul and other artists . The art-work they created was the giant Bingham Mermaid, its shape made from a vast steel armature encased in concrete on which the artists and trainees applied designs made in broken tiles. Now with experience of community collaboration and with skills in sculpture and mosaic as well as painting, Paul joined Theatre Workshop as a community artist. Here he continued for three years working on festivals and play-schemes and added the construction of vinyl inflatables to his abilities.

In 1981 he took time off to carry out a mural commission for Smith and Wellstood iron foundry in Bonnybridge near Falkirk, assisted by part-time Theatre Workshop worker David Wilkinson. “We showed the management what we were going to do, and they were very pleased. It was a large wall, newly rendered and the scaffolding was provided. Its surface was intersected by verticals and horizontals of structure which we absorbed in the painting. Our composition showed a clear look through into the activities within the foundry, concentrating on the demanding and dangerous jobs they were doing. We did drawings and took photographs of them working, and ended up making portraits of many of the workers. We painted it in ten weeks with emulsion paints, which seems crazy now because of the toxic environment coming out of the foundry – it didn’t last that long. There wasn’t a fanfare at the opening, but the owner of the local fish and chip shop, where we had eaten lunch everyday, turned up with bottles Asti Spumante.

the mural restored – a moving event

“I think of it being a community mural although there wasn’t much community involvement born out of their hopes and aspirations, but there was a great deal of fondness for the mural and a sense of loss when the building was demolished unannounced – as these things usually are.”

Later a researcher, Paul Cortapassi, became interested in the mural and its part in the community, tracked down all the best images of the mural and with local funding created a large-scale reproduction of the mural, coated against the elements, which was erected on the front of Bonnybridge Community Centre, together with a key identifying the workers by name. To its opening in May 2016 came workers and a great many wives of workers from the factory.

The Artist’s Collective and Street Artworks.

The same year a new director took over Theatre Workshop and it was clear that murals and environmental art were going against the mainstream; so Paul, Tim and David Wilkinson set up ‘The Artists’ Collective’. On the back of their separate successes in Bonnybridge and Leith, the Scottish Development Agency were persuaded that “to preserve the unity of the community an art input negotiated with the people was essential” and subsequently commissioned public art projects in two areas for community artworks.

In Leith, one project was for the Citadel Youth Centre, working with young people designing and painting metal panels to go around the building. Another was working with local people to design frontages for derelict buildings. On their bricked up windows and boarded shop fronts the artists would create trompe l’oeil images of windows as if still occupied, and in two tower blocks that had become no-go areas for police and fire services, mosaic pictures were made for the foyers after door to door discussions and public meetings.

“The biggest problem was to get through the apathy rather than hostility. Pretty much everything we did was tied into aural history, picking up on generations of people’s understanding of what being a ‘Leither’ meant, becoming acquainted with the place, its family traditions and trades of rope-making, shipbuilding and bottle making. We were trying to find a balance between healthy tradition and nostalgia, and to present an interpretation which was more considered than being a simple mouthpiece of the community’s views.”

finding the community and the design in Dundee

In Dundee the main project was a gable end mural in a run-down industrial area known as Hawkhill. “Our approach, having come from Craigmillar and Theatre Workshop was always to look for community potential for activity. There had been a lot of demolition. Our gable was on St. Peter’s Road at the end of a block of tenement flats, and when we went visiting households you could see it was a fragmented community. But right next door was the primary school, so we made that the centre for our discussions with everyone about the design and development of our mural. We wanted it to be about a sense of place; of Dundee and its employment heritage; of jute, jam and journalism, of rope-making and local stories, and we based the design on a trade union membership certificate that illustrates trades and industries. This time, having seen how poorly emulsions lasted we tracked down a supplier of liquid plastic paint, horrendous to use, but it made an extremely durable mural.” From design discussions to completion the mural took five months, it still exists clearly, even though care-worn, and is well liked by local people.

material for a forward-looking mural

In 1984 David Wilkinson left and Tim and Paul formed ‘Street Artworks’, and carried out their last large scale external painted mural together. It was on a prominent and central “gift of a gable with very interesting bays” on a semi-derelict site in Leith. “What we wanted to do was a forward looking celebration, an encapsulation of how ‘Liethers’ saw themselves in the past and which was projected into the future.” The artists got together with a core of people attached to the Leith Local History Project to collect and look at background materials of anecdotes, memories and photographs, to advise and make proposals for the mural. They met regularly to discuss ideas, the drawings that they had prepared for the overall design and the details as they developed, and to agree to the design that evolved. “Our murial”, as people described it, went on public display in Leith library for final endorsement.

a scheme for the ‘Leither’ mural

Tim and Paul decided they would use Keim silicate paint, which had a reputation for longevity, and which offered advantages in application. As their partnership developed they had achieved a unity of style and a clarity in representation, and the new paint freed their expression. The painting, due to begin in 1985 was delayed by faulty render, so was not completed until the next year. At the very top were pictures of a man, a docker and a woman bottle-worker. Beneath were dockers queueing for work and hunger marchers, men and women with union banners and shipyard workers of all trades and the marches of the 1970’s to save the shipyards. Then came the world of the family, the docker being tended to for a injury, the ‘Carters’ Day Out’, in their dressed carts taking children down to the beach, traditional street games, the Leith Hospital Gala festivities, children’s orchestras in the back-courts of tenements, courtships and marriage, the bookies and the pawnshop. Then the demolition and regeneration of Leith, the new housing, shops and wine bars and a question – where now? – and a joining of hands for the unity of the community. The mural became a landmark, soon to be one among many. Walking tours of murals have become popular in in Leith.

Tim and Paul decided they would use Keim silicate paint, which had a reputation for longevity, and which offered advantages in application. As their partnership developed they had achieved a unity of style and a clarity in representation, and the new paint freed their expression. The painting, due to begin in 1985 was delayed by faulty render, so was not completed until the next year. At the very top were pictures of a man, a docker and a woman bottle-worker. Beneath were dockers queueing for work and hunger marchers, men and women with union banners and shipyard workers of all trades and the marches of the 1970’s to save the shipyards. Then came the world of the family, the docker being tended to for a injury, the ‘Carters’ Day Out’, in their dressed carts taking children down to the beach, traditional street games, the Leith Hospital Gala festivities, children’s orchestras in the back-courts of tenements, courtships and marriage, the bookies and the pawnshop. Then the demolition and regeneration of Leith, the new housing, shops and wine bars and a question – where now? – and a joining of hands for the unity of the community. The mural became a landmark, soon to be one among many. Walking tours of murals have become popular in in Leith.

Paul and Tim continued working together successfully, mostly on projects for museums making coloured figurative reliefs, sculpture and environments, until 1994 when each set up on their own.