Tim was born in Cambridge in 1945. His clergyman father thought of himself as “the last of the parson naturalists.” He was an ornithologist and writer who also had a talent for drawing. Tim’s mother had been a school teacher. She ran the household and organised parish events. Tim describes her as “a saint”. The family lived in a rambling vicarage with attics and box rooms full of curiosities from distant parts of the world. Tim remembers the garden as “glorious for children.” His parents kept chickens and bees, which helped to mitigate the shortages of post-war rationing. “Rationing kept us slim,” he says. They had no car, or TV. A wind-up gramophone and a wireless sufficed for news and entertainment. Holidays were spent in a caravan in the Essex countryside or camping on the Suffolk coast. Tim’s life-long love of the countryside was kindled by these early experiences.

He went to St. Faith’s prep school in Cambridge from the age of seven to thirteen. Latin was compulsory. Art was an optional extra set aside for Friday afternoons. He remembers it as “the only thing that I had a liking for.” He went on to The Leys School nearby. He comments dryly that neither school did him irreparable damage. He scraped into the sixth form with the minimum pass mark, where his talent for drawing was noticed by his biology teacher, who gave him his first opportunity for book illustration. He also suggested that Tim should apply for a place in Cambridge School of Art. (CSA)

relief on leaving the Leys

Accordingly he left The Leys early moving to the two-year Art Foundation Course. “I was relieved to get away, young for my age, and creative. I hadn’t learned anything, so I was keen to start. I was eager to go to a place where learning required making things rather than remembering facts.”

classes in different materials

The Foundation year at CSA included classes in drawing, colour theory, painting, printmaking, graphic design, sculpture, calligraphy, 3D construction and art history. Life drawing and sculpture from the figure were important. Materials included wood, clay, plaster and mixed media, which was typical for the period influenced by the Bauhaus. Tim speaks highly of all the staff there. “Teachers were practicing artists who taught by showing and doing.”

In 1964 Tim moved to Nottingham College of Art to study for the Diploma in Art and Design. The course of three years was newly recognised and was taught by committed painters, sculptors and illustrators. In the second term he was labelled ‘unenlightened’ along with three other students from his year. Apparently, “I was too conventional and had no inner vision.” In fact the college was remarkably tolerant and broad minded, courses included life-size figure sculpture and welding, after which Tim opted for painting as his main subject.

moire’s

He became briefly interested in abstract expressionism before moving to the opposite extreme with hard edge op art, moiré patterns and kinetic illusions. The visiting tutors “were all good”. One of them, Bridget Riley, told him of the inspirational effect ‘scaling up’ would have on his work, a technique that was later vital when painting his gable end murals in Glasgow. He showed his moiré constructions for his final show at Nottingham and was accepted for postgraduate study in the painting school at the Slade School of Art, where his tutor was Robyn Denny. Here he continued making kinetic constructions in which silkscreen imagery was set behind reeded Perspex.

to Glasgow with ‘cutting edge’ constructions

Of his move to Glasgow in 1969 Tim says, “Obtaining a lecturing post at Glasgow School of Art (GSA) was another stroke of luck and quite a culture shock after a cushioned life.” The Director, Sir Harry Jefferson Barnes, was looking for people from England to join the Scottish staff and offered him a post teaching on the two-year introductory course. This was roughly equivalent to the English Art Foundation course. After renting two rooms in a tenement for a time, he moved into a cottage in Waterside, an ex-mining village ten miles outside the city. Families from Glasgow were being rehoused in surrounding villages as ‘comprehensive redevelopment’ destroyed their homes and created dust bowls to make way for tower blocks. It was a time when “Glasgow was being torn apart by demolition.” The displacement moved vandalism, arson and other disturbances into the countryside. “Even in the 1960s it was predictable,” says Tim. “Pruitt–Igoe was dynamited later in St Louis, Missouri. But anyone with sense didn’t have to wait for tower block folly to achieve global notoriety. Expect trouble when you ruin people’s environments, box them in cubes, then split families apart.”

In 1971 the two-year course was shortened to one, which students took before the three-year degree course. The design and painting elements were merged so a greater variety of ideas could be explored. Lecturers pooled their expertise to teach in teams. The year ended with a multiple-choice project, which enabled students to work towards their proposed specialisms. One year Tim’s team set a project to design play areas for children as alternatives to the grim circles of concrete blocks that appeared in several locations in the city. A number of students chose the theme and came up with some excellent ideas, proving as always, that there is no shortage of talent and imagination. However, the people who actually control the built environment often lose whatever imagination they may once have possessed.

after demolition, rendering and the first Glasgow murals

“People’s living spaces were being chopped in half. You could flatten an entire city, but you’d have a lot of rehousing to do, so the bulldozing had to stop at some point. Wherever it stopped gable ends were left with wallpaper and fireplaces hanging intact until some were cemented over leaving enormous flat canvases. Murals began to appear. Stan Bell, at that time leader of the Glasgow League of Artists (GLA), painted one of the first, a pattern of hexagons in black and silver. The GLA was formed in 1971 with the support of the Scottish Arts Council (SAC). Stan’s next mural at George Cross, entitled ‘Hex’, was equally geometric but had more three dimensional illusions. John Byrne’s mural ‘Boy on a Dog’ appeared in 1974, painted in the popular convention of gigantism, where human figures are enlarged up to sixty feet in height. John McColl, another member of the GLA, painted ‘KLAH PII’ in Bellfield Street (1975). It was nicknamed ‘The Frog’ by local residents, though I thought it resembled a robot with claws. About this time another gable painting seemed to be inspired by a Persian miniature. Roger Hoare, who was a tutor in the Mixed Media and Mural Department of the GSA (Glasgow School of Art), painted several murals with students.” In the 1970s most muralists and assistants were male, perhaps indicating biased assumptions that working on scaffolding was not something women do.

design of Tim’s first mural

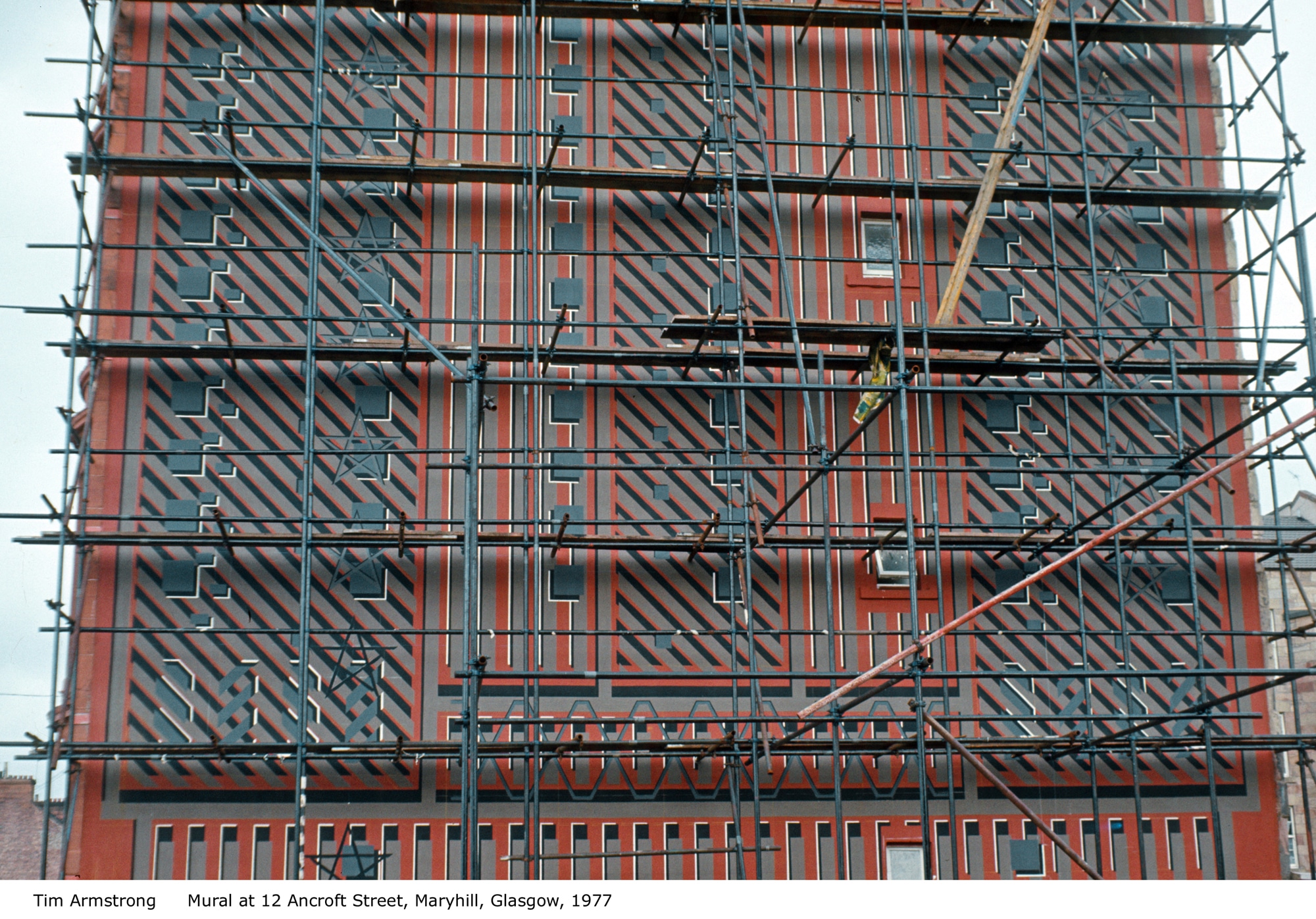

In 1975 an open competition was organised by the Scottish Arts Council for two mural sites in Ancroft Street, Mary Hill. “The tenements were being renovated rather than scheduled for demolition, so I went in for it.” Tim tried to respect the architecture of the city by submitting designs that were modern but fitted in with local colours and styles. “One gable end had relief features – chimney breasts and shoulders – which added interesting elements to the design. I submitted 12 designs based on the colours and architectural motifs visible within a hundred yard radius of Ancroft Street. Features included arches, keystones, brick patterns and cartouches from nearby buildings, some of which were about to be pulled down. The fascias of local shop fronts provided inspiration with their hand-painted shadow writing. I included triple arch motifs from the neo-Romanesque Saint Columba’s Church nearby. Fortunately it is still standing.”

Two of his designs were chosen by SAC and Tim painted them in 1977 with the assistance of artists from the GLA and GSA including John Torjussen, Gregor Smith, Ken Mitchell, Jock McInnes, Peter Bevan, Barry Atherton and John Main. The first mural took four weeks to complete, which reflected the inexperience of artists used to canvases rather than 60 foot walls. The second benefited from the team’s first experience and was completed in two weeks. It was designed like the first, using similar elements, but included the five-pointed star of Bethlehem to acknowledge that it faced the church. Everyone on the team was paid by the SAC. Tim says it was a great experience for him and his friends and feels positively about the work. However muralists have less influence on city environments than architects, and planners. “Alas, what tiny little difference could we make?”

After nine years living, teaching and making artworks in Glasgow, Tim returned to Cambridge, to teach at his old school, Cambridge School of Art. At that time (1982) the Kite area of Cambridge was suffering wholesale demolition comparable to Glasgow’s redevelopment, though on a smaller scale. The local trading association asked the School of Art to paint murals on temporary hoardings outside ‘Laurie and McConnals’, a Grade II listed department store, which was one of the few buildings to be renovated rather than bulldozed. Tim coordinated a competition between students and the trading association selected five of their designs, which were installed by the students with materials donated by the association. Tim comments that art school staff and student’s attitudes to public art were different in Cambridge than in Glasgow. “However, the people who lived in areas of planning blight had much in common. Many painted their own murals to make known their pride and frustration.”

As a result of his experience with murals Tim wanted to work in architectural settings and retrained in stained glass at Central St Martins. He now lives in Saffron Walden, Essex. He is a Fellow of the Society of Designer Craftsmen and divides his time between writing, stained glass commissions and working with 3D mirror constructions.